Surface mutation lets canine parvovirus jump to other species

Canine parvovirus (CPV) emerged as a deadly threat to dogs in the late 1970’s and has since spread to wild forest-dwelling animals. The transfer of the virus from domesticated to wild carnivores has been something of a mystery, until now.

A multidisciplinary team of researchers has identified a mutation in CPV that can profoundly alter transferrin receptor (TfR) binding and infectivity of the virus. The methodology used in this research could blaze a trail for future research into other viruses, including influenza.

Colin Parrish, the John M. Olin Professor of Virology and director of the Baker Institute for Animal Health co-authored a research paper, published in the Journal of Virology, with Susan Daniel, associate professor in Cornell’s Robert Frederick Smith School of Chemical and

Biomolecular Engineering, which contends that a key mutation in the protein shell of CPV – a single amino acid substitution – plays a major role in the virus’ ability to infect hosts of different species.

“That was a critical step,” Parrish explains. “It took a lot of changes to allow that to happen.”

He said another key factor in CPV’s infectivity is adhesion strengthening during TfR binding.

“There’s an initial attachment, which is probably relatively weak. The thing just grabs on and holds on a little bit, sort of like using your fingertips. And then it looks like there’s a second attachment that is much stronger, where it’s like you grab on and hold on with both hands and won’t let go.”

“We think that the second event, this structural interaction that occurs in a small proportion of the binding cases, seems to be critical,” he said. “We think that it actually causes a change in the virus, that it triggers a small shift in the virus that actually makes it able to infect successfully.”

Canine parvovirus has been an area of interest for Parrish since the late 1970’s when he was part of a group of Baker Institute scientists who first isolated the virus and later developed the first vaccine for parvo.

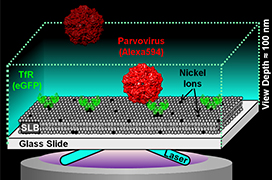

One of Daniel’s specialties is the investigation of chemically patterned surfaces that interact with soft matter, including biological materials such as cells, viruses, proteins and lipids. Her lab has pioneered a method called single-particle tracking – placing artificial cell membranes into microfluidics devices, fabricated at the CNF, to study the effect of single virus particles on a variety of membrane host receptors, in this case from both dogs and raccoons.

“The nice thing about these materials is that we can design them to have all different kinds of chemistries,” she said. “So in this particular study, we can put the receptor of interest in there, isolated from everything else so we can look at the specific effect of that receptor on a particular virus interaction.”

Daniel’s lab also developed the precision imaging devices used in the study.

“Another piece of this paper is how the parvovirus actually sits down and binds even stronger over time with that receptor,” Daniel said. “That was kind of a new result that came out of the technique itself, being able to look at individual binding events.”

Other contributors to the paper included Donald Lee, a graduate student in the field of chemical and biomolecular engineering; Andrew Allison, a postdoctoral associate at the Baker Institute; and Kaitlyn Bacon ’15. Daniel in particular credited Lee and Allison with bringing their individual strengths together in a collaborative way “to make this study happen.”

This work was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation – which also funds the CNF, a member of the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network – and the National Institutes of Health.

This story was adapted from an article originally published in the Cornell Chronicle on April 14, 2016.