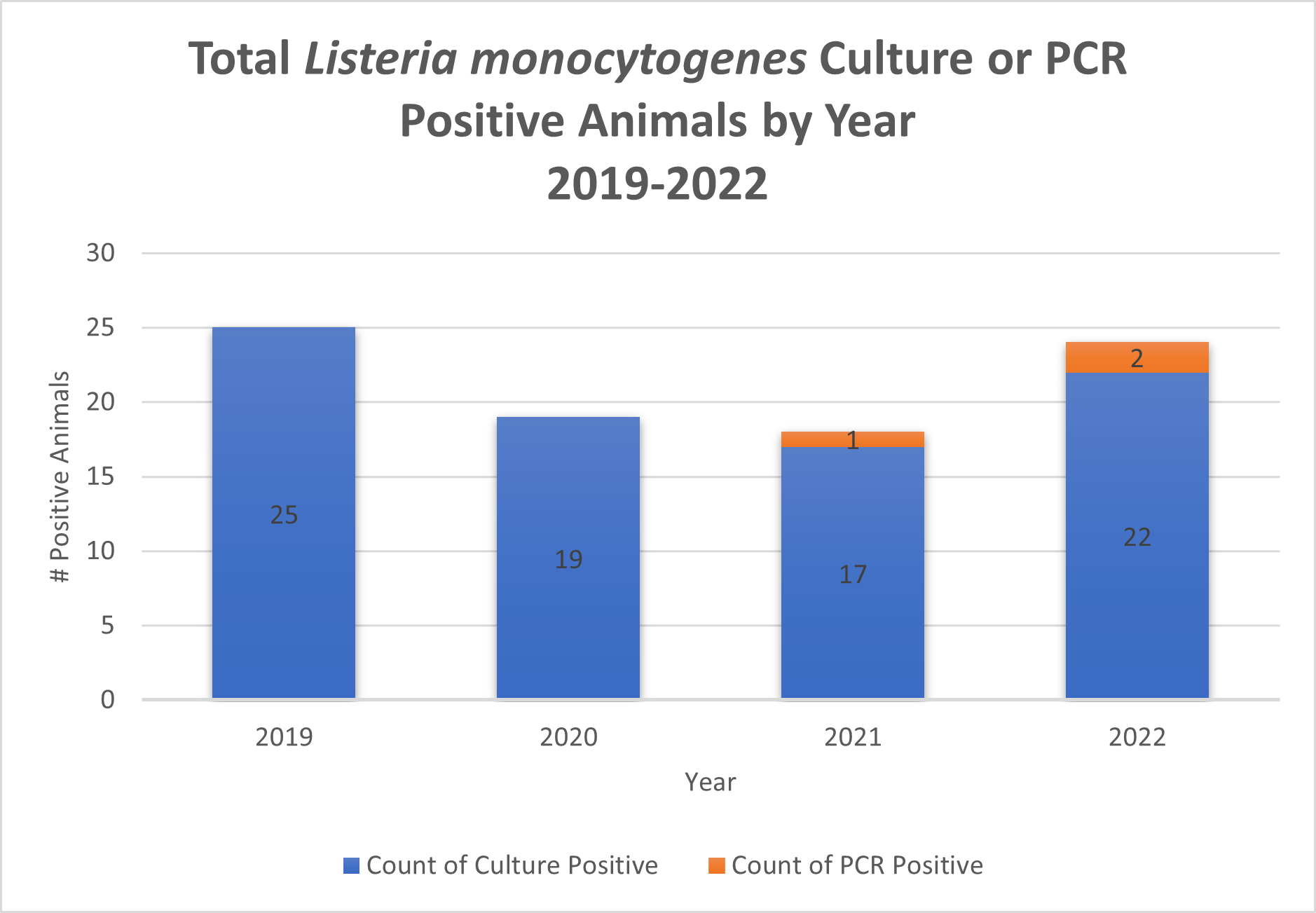

Listeriosis Detected at AHDC from 2019-2022

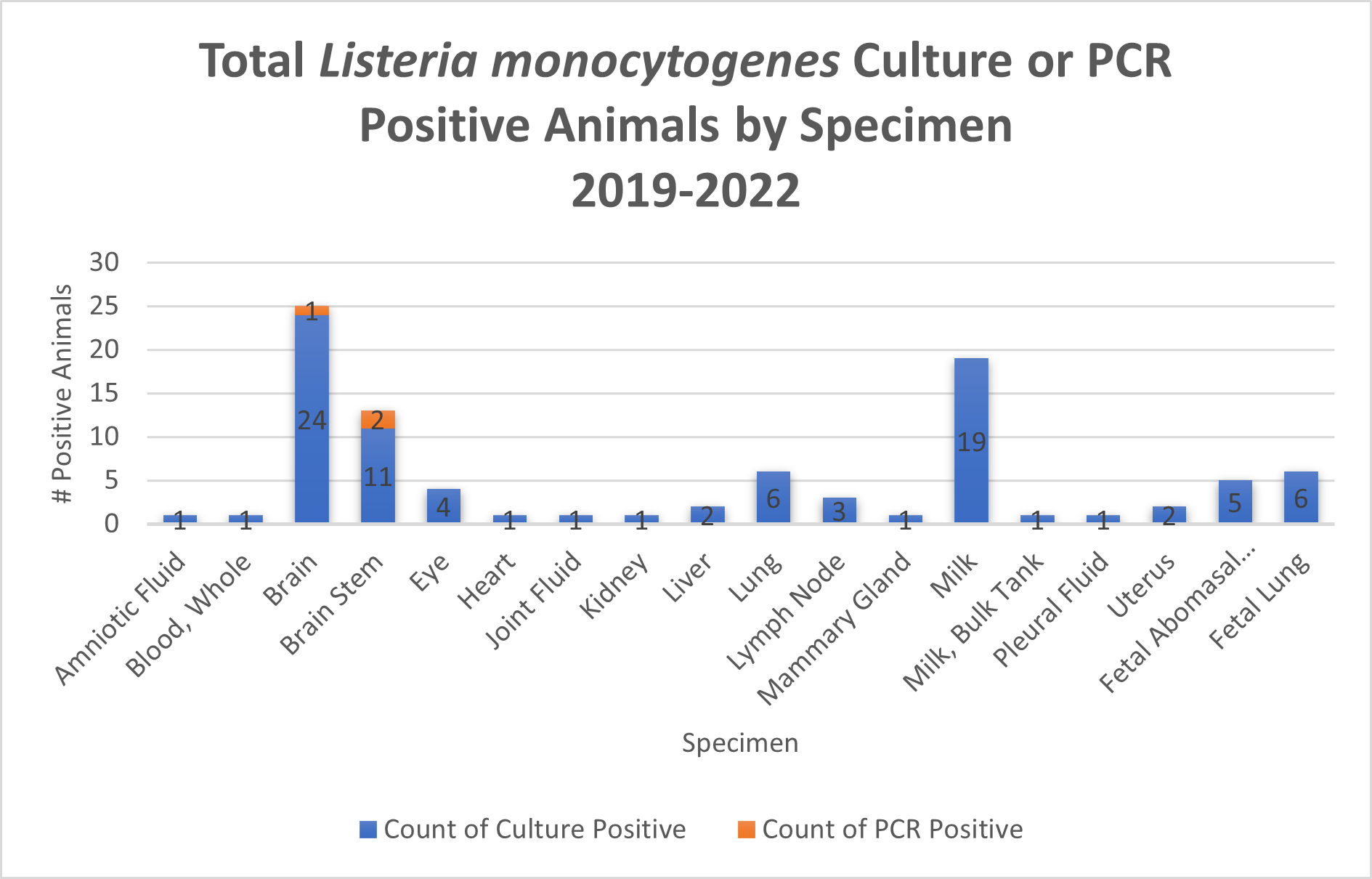

The Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center diagnosed about 20 cases per year of Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) infection by culture or PCR, for the past four years (Figure 1). Most infections were detected in ruminants (91%;78/86), with sporadic cases in equine (n=3), rodents (n=2) and one case each in canine, avian, and wildlife species. L. monocytogenes was isolated from various specimens but was most commonly detected in the brain or brain stem, resulting in a diagnosis of Listeria encephalitis. The remainder of the positive samples consisted of mostly bovine milk samples and fetal tissues from abortion workups (Figure 2).

Listeria monocytogenes is a motile, facultatively anaerobic, gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium that causes listeriosis. Many species can become infected, but fowl, ruminants, and humans are most commonly affected.1 L. monocytogenes are ubiquitous. Ingestion or inhalation of L. monocytogenes from soil, water, vegetation, feces, and contaminated feed, especially due to improper ensiling, are common sources of infection. It is susceptible to common disinfectants but is incredibly hardy in the environment.

Listeriosis occurs worldwide and can manifest as neonatal septicemia, abortions, ocular disease, neurological disease, or even asymptomatic carriers. The most recognized form of the disease is "circling disease" (encephalitis or meningoencephalitis) in adult ruminants.2 Neurological signs are typically unilateral and consist of depression, ipsilateral weakness, and cranial nerve deficits, and can also include circling and recumbency. These animals require early therapeutic intervention because the fatality rate for untreated cases is nearly 100%.

Sampling recommendations for obtaining a diagnosis depend on the form of disease. The diagnosis of encephalitic listeriosis requires postmortem samples. We recommend submitting the brain stem for Listeria culture, as this is the most common location of pathology, specifically the pons and trapezoid bodies.1 L. monocytogenes is not commonly isolated from CSF, but cytology on CSF can sometimes aid in the diagnosis, with high protein and WBC counts associated with a mononuclear pleocytosis, in cases where listeriosis is suspected. CSF should be submitted in EDTA tubes for cytology. In abortion cases, aerobic cultures on the placenta and fetal tissues will yield Listeria if present, assuming the tissues are not overly contaminated. "Silage eye," or an eye infection from L. monocytogenes is confirmed by culturing Listeria from a corneal or conjunctival swab in an animal with keratitis or conjunctivitis.3 Listeria monocytogenes is a zoonotic pathogen, so proper PPE and sample collection strategies should consistently be implemented by veterinarians.

- Smith B, Van Metre D, and Pusterla N. Large Animal Internal Medicine Sixth Edition. Elsevier, 2020.

- Constable, P. Listeriosis in Animals. Merck Veterinary Manual, Jun 2021.

- Evans K, Smith M, McDonough P, Wiedmann M. Eye infections due to Listeria monocytogenes in three cows and one horse. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004 Sep;16(5):464-9. doi: 10.1177/104063870401600519. PMID: 15460335.

Figure 1. Number of animals that tested positive for Listeria monocytogenes via culture or PCR received by the Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center from 2019-2022.

Figure 2. Specimens used to detect Listeria monocytogenes from the positive animals received by the Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center from 2019-2022.

Figure 2. Specimens used to detect Listeria monocytogenes from the positive animals received by the Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center from 2019-2022.