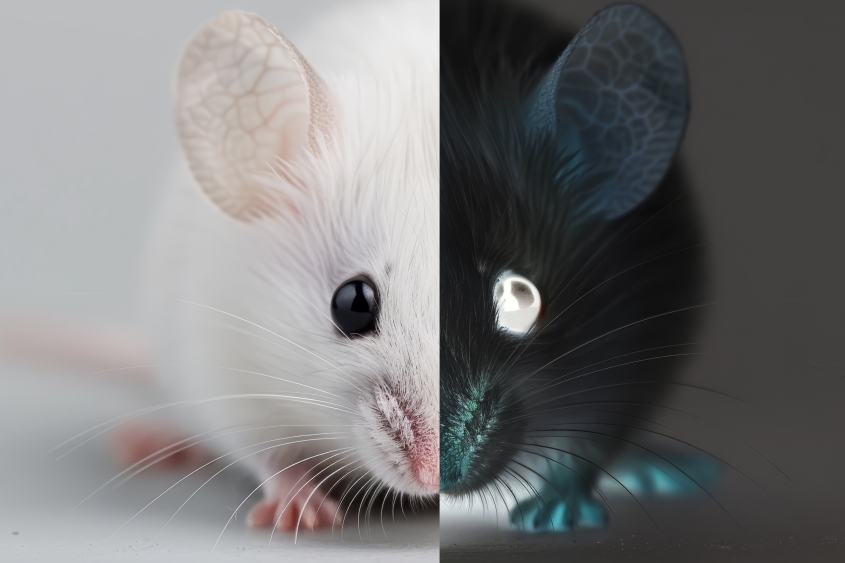

Is that mouse sick or healthy? Pick a side

Researchers at Cornell are developing a mouse model – called UMos, short for unilateral mosaic – that are designed to have only one side of their body affected by diseases, offering a transformative way to do research on bilateral or pairs of organs, like the lungs for example.

“With these mice, we can direct a disease to only one side of the organs,” says David Gludish, Ph.D. ’17, D.V.M. ’20, senior research associate in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, who is leading the project. “For some studies, we won’t have control animals, we will have control tissues. This is an amazing set up.”

An added benefit of being able to compare the two sides of the same animal is that the number of mice involved in an experiment can be halved. In addition, Gludish says, comparing the left and right of the same mouse will also reduce environmental variations that may affect the results, like the cage in which the disease and control animals are kept in, for example. This will further reduce the number of mice required in the experiment to gain statistical power.

“If we don’t need a control and a disease group, the number of animals involved in research will be reduced dramatically.”

The UMos mouse model was developed in collaboration with Dr. Natasza Kurpios, professor in the Department of Molecular Medicine, who is an expert on internal organ development and left-right asymmetry.

This proof-of-concept research is funded by a NIH R21 grant from the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, a branch of NIH that supports the development of resources applicable to many disciplines of research. And this is exactly what UMos mice are designed to do, allowing researchers all around the world from many disciplines to work on paired or asymmetric organs, like the lungs, heart, and liver.

When researchers develop a mouse model, it is generally to study a particular disease or biological system, says Gludish. “Here, this is the opposite, this model is designed be useful to different researchers in multidisciplinary fields and appeal to multiple NIH institutes.”

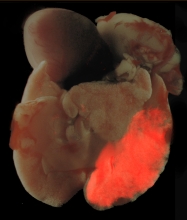

The first set of UMos mice will be engineered to express the human receptor for SARS-CoV2 on one side of the lung. Gludish wants to demonstrate that the UMos mice will only be susceptible to disease on one side of their lungs, and that these mice will survive thanks their other healthy, non-infected lung despite receiving a high viral dose that would otherwise be lethal in regular mice. This will achieve the double goal of further decreasing animal casualties, and answering questions around “long COVID” or tissue recovery after severe COVID infections.

Gludish will use another set of UMos mice to study breast cancer metastasis in the lung. These UMos mice are built to express genes known to create environment conductive to metastasis differently on the right and left lung. Gludish predicts that metastatic breast cancer cells injected in the blood of UMos mice will settle predominantly on one side of their lung. This part of the project is developed in collaboration with Dr. Claudia Fischbach, the Stanley Bryer 1946 Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the College of Engineering. At CVM, Heidi Reesink, Ph.D. ’16, another consulting participant on the grant, plans to use UMos mice to study bone and joint diseases.

Over time, Gludish would like UMos mice to aid the study many diseases that affect specific organs. Most organs have a left and a right side that are determined early in the embryo development, he says, even the liver. “We could, for example, confine some disease to one half of the liver, and compare the impact of therapies on the diseased half versus the healthy half – all in the same animal,” says Gludish.

“Our model is not designed to answer one particular question, it is designed to answer as many questions as we can imagine,” he says. “If researchers use their creativity, the sky is the limit.”

Written by Elodie Smith