Could “arresting” ovaries be the next contraceptive? The Cohen lab plans to find out

Women’s contraception is more important than ever. But current methods can be plagued with side-effects and barriers to access for some women. To develop an effective non-hormonal contraceptive, Dr. Paula Cohen, professor of genetics, director of the Cornell Reproductive Sciences Center and associate dean for research and graduate education, has received a grant from the Gates Foundation for $1.5M over two years to find potential therapeutic targets within the ovaries.

“The ovary is likely to be the only target organ for women that will allow us to develop long-acting contraceptives,” says Cohen.

Cohen is part of the non-hormonal contraception (NHC) group, a consortium formed by the Gates Foundation, which focuses on developing contraceptives without side effects of the traditional pill. For Cohen, that means pinpointing the proteins that keep the egg in its “arrested” state, with the hope of creating a drug that can hit pause on egg development and thus prevent ovulation.

But finding these proteins is tricky; traditional laboratory methods like mass spectrometry only allow scientists to look at all proteins in a tissue, rather than individual cells. “It’s not possible to discern these discrete protein signals from single egg cells from all the rest of the noise in the ovary,” says Cohen. “We have lacked the tools to understand how some oocytes remain dormant while others progress into ovulation.”

To resolve this problem, Cohen and her colleagues, including Dr. Haiyuan Yu, professor with the Weill Institute and director of the Cornell Center for Innovative Proteomics, are using the grant funding to employ cutting-edge technology that allow single cell proteomics, which categorizes all the proteins of just one cell — otherwise known as the proteome.

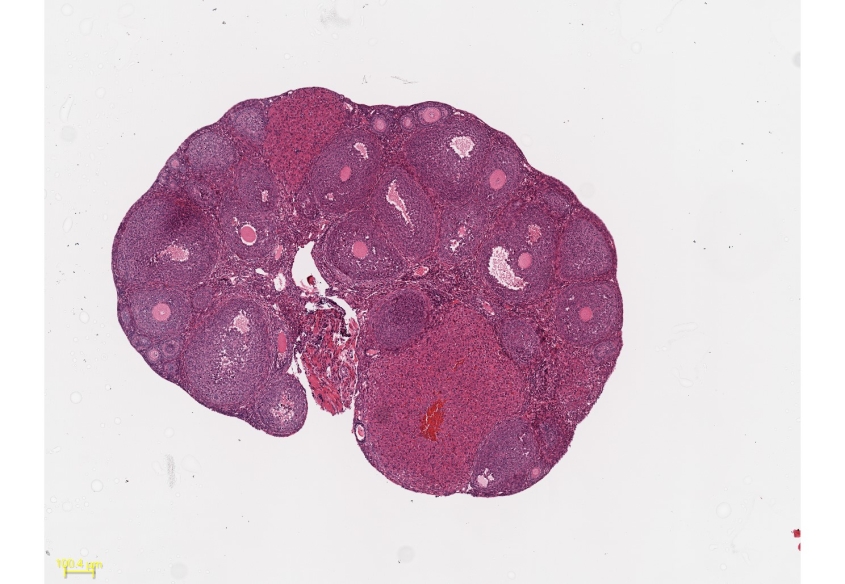

They plan to look at the proteomes of eggs and their supporting cells (collectively forming an ovarian follicle) of both mouse and human ovaries at different stages of development. “Using the power of single-cell proteomics, we will define the dynamic ovarian proteome, from arrested follicles through to ovulating follicles,” Cohen says.

The team will also establish follicle culture techniques in the lab, so that potential protein targets can easily be tested in vitro from the earliest stage of development right through to ovulation.

“Ultimately, the goal is to identify a set of novel proteins that can be evaluated for their role in follicle development and ovulation,” says Cohen. “For each of those proteins, we will determine how it is expressed through all those developmental stages, both in mouse and human adult ovaries, with the aim of finding prime therapeutic targets.”

Cohen’s team will share those potential protein targets with NHC consortium colleagues to develop new tools and assays for testing their feasibility and viability. “After that, the goal is to develop small inhibitory molecules against the protein target,” says Cohen.

With any luck, those molecules could be the future of non-hormonal contraception.

Written by Lauren Cahoon Roberts