Feline Leukemia Virus

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) is one of the most common and important infectious diseases in cats, affecting between 2-3% of all cats in the United States and Canada. Infection rates are significantly higher (up to 30%) in cats that are ill or otherwise at high risk (see below). Fortunately, the prevalence of FeLV in cats has decreased significantly in the past 25 years since the development of an effective vaccine and accurate testing procedures.

Transmission

FeLV is a type of virus called a retrovirus, meaning it can be incorporated into a cat’s genome and may not be cleared over time. Persistently infected cats shed infectious viral particles in saliva, as well as in feces, urine and milk. Any close contact among cats can spread FeLV, including bite wounds, mutual grooming, or sharing feeding dishes and litter boxes. Transmission can also take place from an infected mother cat to her kittens, either before they are born or while they are nursing. FeLV does not survive long outside a cat's body – probably less than a few hours under normal household conditions - so it is unlikely for a cat to be infected from the environment without prolonged close contact with an infected cat.

Cats at greatest risk of FeLV infection are those that may be exposed to infected cats, either via prolonged close contact or through bite wounds. Such cats include cats living with infected cats or with cats of unknown infection status, cats allowed outdoors unsupervised where they may be bitten by an infected cat, and kittens born to infected mothers. Though any cat exposed to the virus can develop an FeLV infection, kittens are at a greater risk than adult cats due to their immature immune system.

Outcomes of Exposure

After exposure to FeLV, a cat’s body can react to the virus in a few different ways, leading to abortive, regressive, or progressive infections.

In some instances, a cat can mount an effective immune response against the virus and completely eliminate it before the virus becomes incorporated into the cat’s genome. This is considered an abortive infection, and all direct testing for the virus will be negative. These cats will have antibodies against FeLV and are considered immune to the disease. Abortive infections were once considered quite rare but studies using newer testing methods show that at least 20-30% of cats exposed to FeLV develop an abortive infection. These cats will never test positive for FeLV using any routine tests or show clinical signs of the disease, so owners and veterinarians may never be aware that they were ever infected by the virus.

About 30-40% of cats have a partially effective immune response following exposure to the virus and develop a regressive infection. In these infections, the virus is incorporated into the cat’s genome, but the immune system prevents prolonged viral replication, so there are no viral particles present in the cat’s blood after the initial infection. While a cat has a regressive infection, it cannot actively infect other cats with the disease, and it is very unlikely to experience clinical signs from FeLV. However, it is possible for the virus to reactivate and start replicating again, especially if the cat becomes immunosuppressed through illness or medications. When this happens, the cat is again infectious to other cats and at risk of developing clinical illness.

Progressive FeLV infection carries the worst prognosis, and cats with progressive FeLV are at high risk of developing potentially fatal associated diseases. With a progressive infection, a cat’s bone marrow becomes infected with the virus and allows for continual viral replication. Cats with progressive FeLV infection shed viral particles and can infect other cats. Studies suggest that 30-40% of cats exposed to FeLV develop a progressive infection, but kittens are at much higher risk of developing progressive disease than cats exposed to the virus as an adult.

Diagnosis

Because of the different ways a cat’s body can react to FeLV infection, more than one test is generally required to accurately diagnose the disease. No single test at one time point is sufficient to determine if a cat has a progressive FeLV infection.

Two types of blood tests commonly used to diagnose FeLV detect a protein component of the virus called FeLV P27. One of these tests, called an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), is usually performed first as a screening tool, and can be run in a veterinarian's office. ELISA-type tests detect the presence of free FeLV particles that are commonly found in the bloodstream during both the early and late stages of infection.

The indirect immunofluorescent antibody assay (IFA) test detects the presence of P27 protein within white blood cells and platelets (incorporation of virus into these cells takes place during progressive infections after the bone marrow is infected) . Importantly, false positive results are possible for both of these protein-detecting tests, so follow up confirmatory testing is always recommended if an initial screening test returns a positive result.

A positive ELISA and/or IFA result suggests that a cat has an active FeLV infection with viral replication, which means there is either an early-stage infection, or a progressive infection. In cats with a progressive infection, these tests will remain positive when rechecked several weeks to months later. If the cat develops a regressive infection, both the ELISA and IFA will give negative results when the virus is no longer replicating.

A third type of test, called a polymerase chain reaction (PCR), can detect if the virus has been incorporated into the cat’s genome, even if the virus is not currently replicating. This test will remain positive for regressively infected cats and is the recommended follow-up test to confirm a positive screening ELISA test.

It is important to note that all of these tests can give a false positive result with very recent infection, so if there is concern over recent exposure to FeLV the test should be repeated in 3-6 weeks to ensure accuracy. Most positive tests should have follow-up testing performed 6-12 weeks later to determine if the FeLV infection is progressive or regressive.

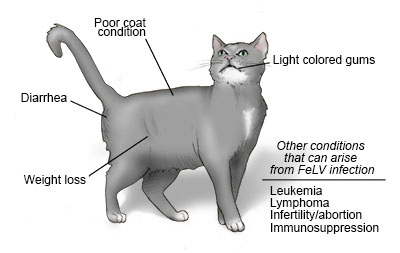

Clinical Signs

FeLV adversely affects a cat's body in many ways. It is the most common cause of cancer in cats, may cause various blood disorders, and may lead to a state of immune deficiency that hinders a cat's ability to protect itself against other infections. Because of this, common bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and fungi that usually do not affect healthy cats can cause severe illness in FeLV-infected cats. These secondary infections are responsible for many of the diseases associated with FeLV.

During the early stages of infection, it is common for cats to exhibit no signs of disease at all. Over time, however, (weeks, months, or even years) an infected cat's health may progressively deteriorate or he/she may experience repeating cycles of illness and relative health. Signs can include:

- Loss of appetite

- Progressive weight loss

- Poor coat condition

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Persistent fever

- Pale gums and other mucus membranes

- Inflammation of the gums (gingivitis) and mouth (stomatitis)

- Infections of the skin, urinary bladder, and upper respiratory tract

- Persistent diarrhea

- Seizures, behavior changes, and other neurological disorders

- A variety of eye conditions

- Abortion of kittens or other reproductive failures

A cat with progressive infection is most at risk of developing these clinical signs, but a cat with regressive infection can also develop FeLV associated diseases if the virus reactivates.

Treatment and Prevention

Although there are some therapies that have been shown to decrease the amount of FeLV in the bloodstream of affected cats, these therapies may have significant side effects and may not be effective (or available) in all cases. Unfortunately, there is currently no definitive cure for FeLV. Veterinarians treating and managing FeLV-positive cats showing signs of disease usually treat specific problems (like prescribing antibiotics for bacterial infections, or performing blood transfusions for severe anemia).

The only sure way to protect cats from FeLV is to prevent their exposure to FeLV-infected cats. Keeping cats indoors, away from potentially infected cats is recommended. If outdoor access is allowed, provide supervision or place cats in a secure enclosure to prevent wandering and fighting. All cats should be tested for FeLV prior to introducing them into a home, and infection-free cats should be housed separately from infected cats. Food and water bowls and litter boxes should not be shared between FeLV-infected cats and non-infected cats. Unfortunately, many FeLV-infected cats are not diagnosed until after they have lived with other cats. In such cases, all other cats in the household should be tested for FeLV. Ideally, infected and non-infected cats should then be separated to eliminate the potential for FeLV transmission.

Vaccination for FeLV is available, and although it will not protect 100% of cats vaccinated, it is recommended to reduce the risk of FeLV infection for cats at risk of exposure, such as indoor/outdoor cats. This vaccine is also now considered a core vaccine for kittens, due to their higher risk of developing progressive infection. Owners contemplating FeLV vaccination for their uninfected cats should consider the cats' risk of exposure to FeLV-infected cats and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of vaccination with a veterinarian. Since not all vaccinated cats will be protected by vaccination, preventing exposure remains important even for vaccinated pets. FeLV vaccines will not cause false positive FeLV results on ELISA, IFA, or any other available FeLV tests.

Prognosis

Although a diagnosis of FeLV can be emotionally devastating, it is important to realize that cats with FeLV can live normal lives for prolonged periods of time. The median survival time for cats after FeLV is diagnosed is 2.5 years, but this can be much longer for cats who develop a regressive infection. Once a cat has been diagnosed with FeLV, careful monitoring of weight, appetite, activity level, elimination habits, appearance of the mouth and eyes, and behavior is an important part of managing this disease. Any signs of abnormality in any of these areas should prompt immediate consultation with a veterinarian.

Updated 2024