Experts develop genetic test to predict severe digestion disorder in German Shepherd dogs

When puppies are about 4 weeks old, they start weaning off their mother’s milk and progress to solid foods. However, some dogs are born with a genetic condition that enlarges the esophagus and impedes their ability to swallow. These pups regurgitate every time they try to eat, and in severe cases, this disorder can cause fatal complications.

Now, scientists are one step closer to understanding the genetic predispositions behind the condition, called congenital idiopathic megaesophagus (CIM). New research used a genome-wide association study to identify a repeating DNA sequence on canine chromosome 12 that shows a strong connection to the presence of CIM in German Shepherd dogs, due to its role in gastrointestinal motility and appetite.

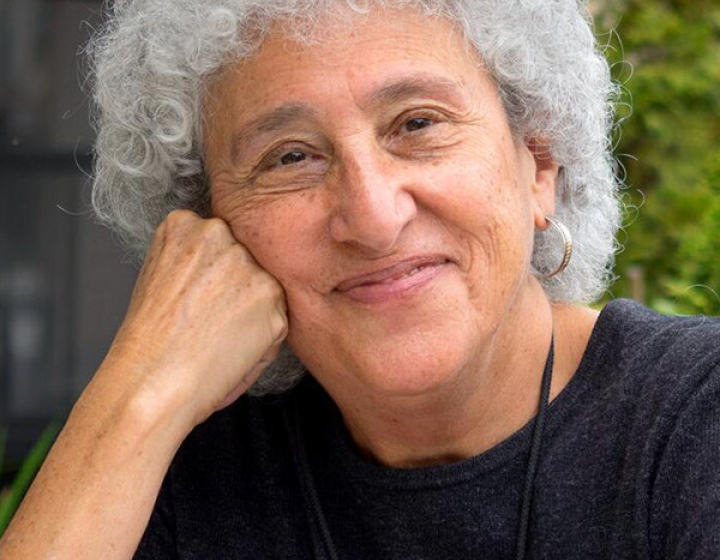

“Understanding the genetics behind this disease not only allows us to develop a genetic test, but also tells us more about how it develops — which can lead to targeted treatments,” said Dr. Jacquelyn Evans, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, where she’s based at the Baker Institute for Animal Health.

Evans is a co-author on the study, which she completed during her time at Clemson University and the National Institutes of Health. The team’s findings titled, “Congenital idiopathic megaesophagus in the German shepherd dog is a sex-differentiated trait and is associated with an intronic variable number tandem repeat in Melanin-Concentrating Hormone Receptor 2,” published in PLOS Genetics on March 10.

The study also revealed that males are twice as likely as females to develop the disease, and the researchers think that lower estrogen levels may explain why males have a higher risk for CIM than females.

A ring of soft muscle connects the esophagus to the stomach, relaxing and contracting to help mammals swallow. Similar digestive studies in humans have shown that the hormone estrogen plays a key part in relaxing this muscle to increase the motility of food through this passage. If this process works the same way in dogs, then females would be partially protected from developing CIM due to their higher estrogen levels naturally present in this muscle.

While CIM affects German Shepherd dogs more than any other breed, it’s commonly found in Labrador Retrievers, Great Danes, Dachshunds and miniature Schnauzers too.

As part of the study, the scientists developed a genetic test to identify the overall risk for CIM in German Shepherd dogs, which will allow breeders to make more informed decisions and reduce the chances of future litters inheriting the disease. Evans said it's important to understand how this condition affects service dog breeds in particular — because their trainers primarily use food as a reward, as opposed to toys or play.

“This is a highly intelligent and trainable breed utilized in many different capacities, such as scent detection, guiding the blind and protection,” she said. “Future work will determine if the gene is under selection in the breed for its role in food motivation.”

Additional studies will also focus on identifying the genetic risk factors for CIM that are specific to other breeds.

Funding for this research was provided by the Collie Health Foundation, the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation, the Upright Canine Brigade, the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Evans is also part of the Cornell Richard P. Riney Canine Health Center at the College of Veterinary Medicine. Learn more about the study in this press release.

Written by Jana Wiegand