Renaissance woman Mary Smith ’69, D.V.M. ’72, awarded college’s highest alumni honor

When Mary Smith ’69, D.V.M. ’72, was in sixth grade, she thought it was high time to pick her profession. “I realized I HAD to decide — I’m either going to be a veterinarian or a botanist,” says Smith. Her fauna versus flora dilemma was influenced by her parents — her father worked at Cornell’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences studying poultry disease, while her mother had training and deep knowledge of botany.

Lucky for the veterinary profession, Smith decided to follow her animal-driven interests. Over half-a-century since that decision, the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) Alumni Association has awarded Smith the college’s highest alumni honor: The Daniel Elmer Salmon Award for Distinguished Alumni Service. The award recognizes veterinary graduates who have distinguished themselves in service to the profession, their communities or to the college. It was established by the CVM Alumni Association in 1986 and named in honor of Cornell's first D.V.M. graduate. Salmon is best remembered for his pioneering work in controlling contagious animal diseases in the early twentieth century, and the bacterium salmonella was named in his honor.

“Dr. Smith provides exemplary service to D.V.M. students, veterinarians and the profession,” says Lorin D. Warnick, D.V.M., Ph.D. ’94, Austin O. Hooey Dean of Veterinary Medicine. “She is an exceptional graduate of the college and very deserving of the award.”

Keith Blackmore, D.V.M.’79, a former student and friend, nominated Smith for the recognition, stating, “Mary Smith is not just a stand out, she is a stand alone. She has demonstrated unsurpassed dedication to students and to farm clients for nearly half a century, and is referred to as legendary.”

The accidental trailblazer

Smith’s journey to the veterinary profession began at a time when the field was highly unwelcoming of women. When she came for her veterinary school interview at Cornell, the administration had already set aside spots for 58 men before interviewing four women for the two remaining slots.

This systemic sexism didn’t bother Smith much, though, who held her own easily in male-dominated spaces during her undergrad years at Cornell — including in the outdoor club, where she eventually became student president. “I was used to being treated as an equal,” she says.

In fact, Smith credits the school’s bias against women for helping direct her to her destiny: The sign-up sheets for summer jobs in the small animal hospital were posted only in the men’s locker room at the time, meaning she never knew that the opportunity existed. Instead, Smith ended up volunteering over two summers with the ambulatory service — the service she would eventually go on to influence for decades.

Smith says she has few memories of unequal treatment, even when she became the first woman clinician to work in Cornell’s ambulatory and large animal practice. One does stand out, however. Smith and a student went to investigate a farm that was rumored to have badly mistreated livestock. The twin farmers — one holding a shotgun, no less — refused to talk to Smith, conversing only with her male veterinary student.

Beyond that menacing moment, Smith is indifferent about her trailblazing status. “If there was discrimination, I’m not socially aware enough to notice,” she says.

Goat notes and beyond

While Smith has extensive knowledge of most large animal species, she is renowned for a particular area of expertise. “Mary has an enormous range of knowledge in large animal veterinary medicine, but she is the international expert with respect to the management and veterinary care of small ruminant species,” says Dr. Carolyn McDaniel, professor of practice in veterinary curriculum.

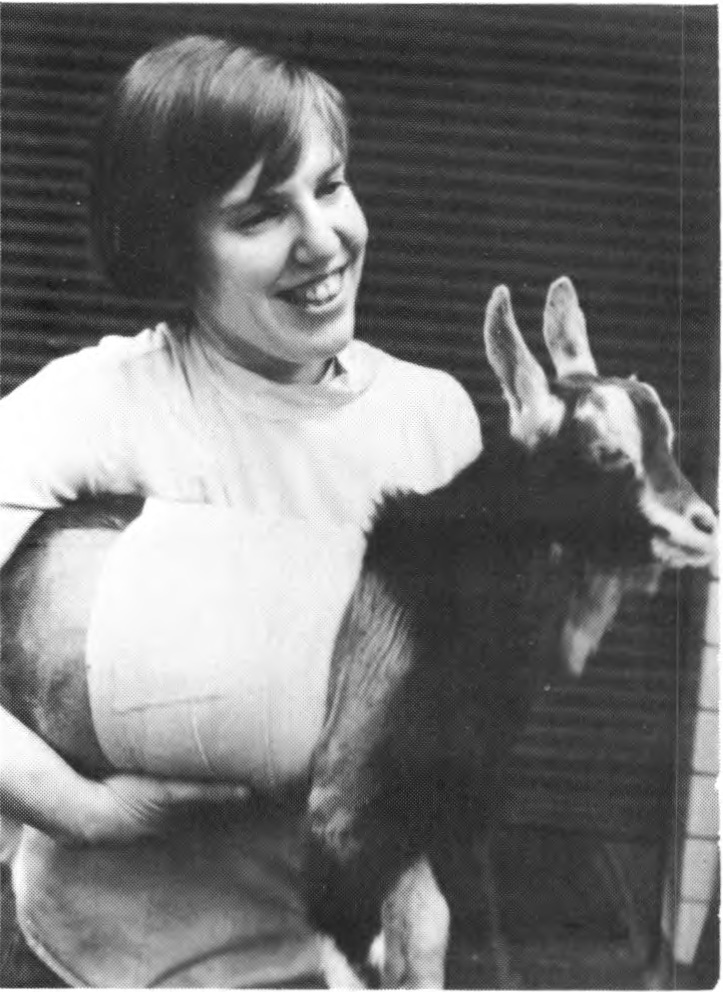

A series of serendipitous events led to this specialization, one being a certain student in her class, Katharine Wilderoter, D.V.M. ’76, who harangued her for answers on goats. “I have to give credit to Kathy,” Smith says. “She had nine goats and a VW that didn’t start. Every large animal class when anyone lectured, her hand would go up — ‘and what about goats?’ — we’d say ‘Down, Kathy. We cannot tell you because we don’t know the answer to your question!’”

Wilderoter’s persistence drove Smith to seek answers, and she assigned a group of interested students to meet in the evenings after looking up the literature on different facets of goat medicine. When they’d return with their information, Smith typed it up into a now-legendary document known informally as her ‘goat notes.’

Momentum grew from there, with Smith embarking on a scholarly exchange trip to France where she worked as a researcher at the National Institute for Agricultural Research near Paris, France. As part of her work, Smith was tasked with taking blood samples from a herd of research goats. Samples were collected every four hours, and Smith just happened to be given the night shift, but this didn’t bother her one bit. “I learned how to bleed goats in the dark — I knew that the vials were full when they turned warm.”

Smith eventually went on to publish a paper in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association on mastitis in goats, followed by many other peer-reviewed articles on small ruminant health and medicine, and the textbook “Goat Medicine,” which Smith and coauthor David Sherman will be releasing in its third edition of this summer.

In 1986, Smith deepened her expertise by going on sabbatical in Germany at University of Munich, where she continued her focus on small ruminants. She has also contributed to the field by serving as editor of the American Association of Small Ruminants newsletter, Wool and Wattles, and moderates the group’s very active listserv.

Happy in ambulatory

For some faculty members, developing such expertise might lead them away from hands-on clinical practice and into their offices or laboratories; not so for Smith. For over four decades, she has driven thousands of miles around Tompkins County and beyond visiting clients’ farms as an ambulatory veterinarian.

Her introduction to the farm vet life started all those years ago — when she missed the job posting for the small animal hospital job, and instead found herself riding along with Robert Hillman, D.V.M. ‘55, professor and renowned large animal theriogenologist. For two summers, Smith got Hillman’s excellent training in fieldwork and getting to know the farmers.

After graduating CVM, Smith stayed at Cornell to work as an intern in the ambulatory clinic. “She excelled as a large animal clinician,” says Hillman, adding that Smith “has proven to be an excellent diagnostician and her quiet approach and confident handling of her patients has resulted in an exceptional success rate.”

For Smith, the ambulatory life holds great appeal. “I like being paid to go visit my friends,” she says with a smile. Driving down the road with students in tow, she’ll quiz them on plants whizzing by (“I can identify them going by at 55 mph — the students have a tougher time with it.”) As for clinical work, Smith’s enthusiasm for it has not been dampened by time.

When asked for her most memorable stories from her career, Smith is at a loss. “There are so many, I don’t know how to pick one.” She rattles off accounts of amorous Bactrian camels, of a white goose loose in her car, of swimming goats.

Colorful anecdotes aside, Smith’s dedication to ambulatory medicine is stuff of legends as well. “Dr. Mary Smith is the ambulatory service incarnate,” says Michelle Stefanski-Seymour, ambulatory technician. “Large animal medicine comes with its hazards. Dr. Smith would often still practice with a black eye, a burn to the arm from a dehorner when a student block failed, and various bandages and splints.”

“She is a very hard worker, always looking to take on more clients and new challenges,” says Hillman.

Cornell colleague Dr. Nita Irby, Ruttenberg Senior Lecturer Emerita in the Section of Ophthalmology, echoes the sentiment. “She is known for endlessly seeking answers to improve the health and welfare of her patients. She never, ever leaves any problem or question unanswered.”

Dr. Maurice “Pete” White, who worked with Smith on the ambulatory service for three decades, recalls,“She was seemingly tireless in responding to telephone (back in the day) requests for assistance from veterinarians and owners,” says White. “The Salmon Award is for service, and that was service at a very high level.”

As a college icon, Smith is known for more than just professional accomplishments. Her colleagues speak fondly of her mismatched socks and disorganized office, of her famous frugality and tendency to break into song at any given moment. Away from the CVM hallways, Smith practices her fluency in French and German, and is learning Spanish and

Swedish; she plays the French horn with the Ithaca Concert Band; and (along with her Cornell physicist husband Eric) is a world champion in the sport of rogaine orienteering — an outdoor navigational race — and was just recently named 2021 North American champions in the long-distance “ultra-veteran” category.

“She is a modern-day Renaissance woman,” says Stefanski-Seymour.

Always a teacher

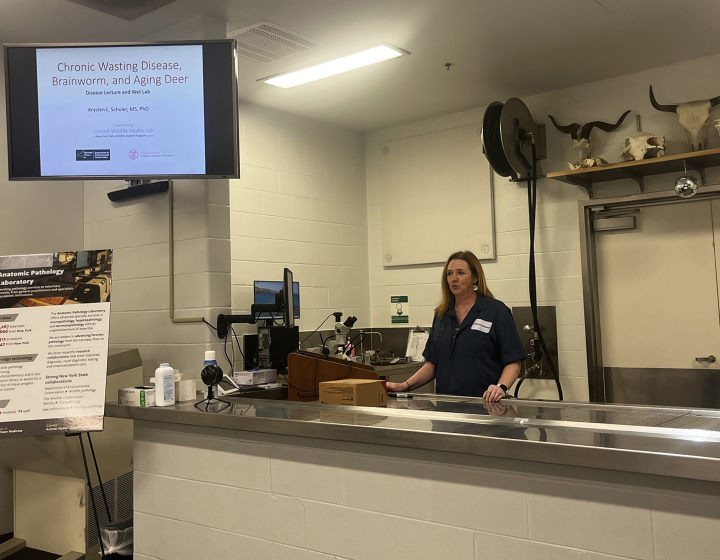

Smith’s iconic status is also due in part to her commitment to students. In addition to mentoring fourth-year students in the ambulatory rotation, she also teaches the sheep and goat medicine, poisonous plants and camelid distribution courses, as well as teaching in the core curriculum, leading the senior seminar course, organizing the food animal welfare and alternative medicine courses.

Warnick describes Smith’s exemplary dedication to teaching the next generation. “She works tirelessly to ensure that students receive constant, diverse, training opportunities both in the field and in the classroom. This includes assessing student progress using oral examinations, one of the few faculty members to carry this tradition forward in the footsteps of another teaching legend, Dr. Alexander de Lahunta,” he says. “I am confident that any graduates over the decades of her time on the faculty will remember her teaching with fondness and appreciation.”

This theme — that Smith’s prolific teaching career has influenced countless veterinarians over the years — is mentioned again and again by those who know her.

“When I think about the number of students Dr. Smith has trained, encouraged and challenged, and the impact those students (now veterinarians) have had in their respective careers, I am amazed at her influence,” says the ambulatory clinic’s section chief Jess McArt, D.V.M. ’07, Ph.D. ’13. “Everyone has a Mary Smith ambulatory story. They make the best dinner conversations, stories at the White Coat Ceremony and memories at reunions. And each individual telling these stories learned something that made them a better veterinarian.”

“I don't know another faculty member who has taught longer and with undiminished enthusiasm for reaching the hearts of our students,” says Charles Guard, D.V.M. ’80, former fellow clinician on the ambulatory service.

McDaniel agrees. “Generations of D.V.M. students have memories and stories of their time on ambulatory calls with Dr. Smith,” she says. “Mary’s unique style is legendary, but her value to students is due to much more than style. She uses each farm visit as a way to share her broad view of the role of the veterinarian, the needs and expectations of the client, and (most of all) the context and specifics of the medical issues encountered on the farm.”

Warnick attests to Smith’s indefatigable dedication to all that she does. “Having had a neighboring office to Dr. Smith for several years, I observed the long hours of work preparing lectures and teaching materials, the evening calls to practitioners in need of advice and her generosity in consulting on cases in the veterinary teaching hospital,” he says. “She approached every situation with thoroughness, scientific rigor and constant pursuit of new knowledge to benefit animal health. She is one of those faculty who will leave an indelible positive impression on everyone she worked with.”

Written by Lauren Cahoon Roberts