Leopold’s legacy: Wildlife health a key component to conservation

A new perspective piece from the College of Veterinary Medicine highlights the vital relationship between wildlife health and the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

“Some of our greatest conservation thinkers understood that health was a key part of conservation, but until now, its connection to the model that governs how we care for animals and plants in North America has largely been overlooked,” said Dr. Robin Radcliffe, associate professor of practice in wildlife and conservation medicine. “Figuring out a sustainable, healthy relationship between humans and the natural world has so far eluded modern society, and I can’t think of anything more important than that in light of recent events.”

This new perspective piece by Radcliffe — alongside co-author Dr. David Jessup of the University of California at Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine, Wildlife Health Center — was published in the Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine Sept. 26. It reviews the current model and its history, posits wildlife health as a crucial missing piece, offers precedent and a path for moving forward.

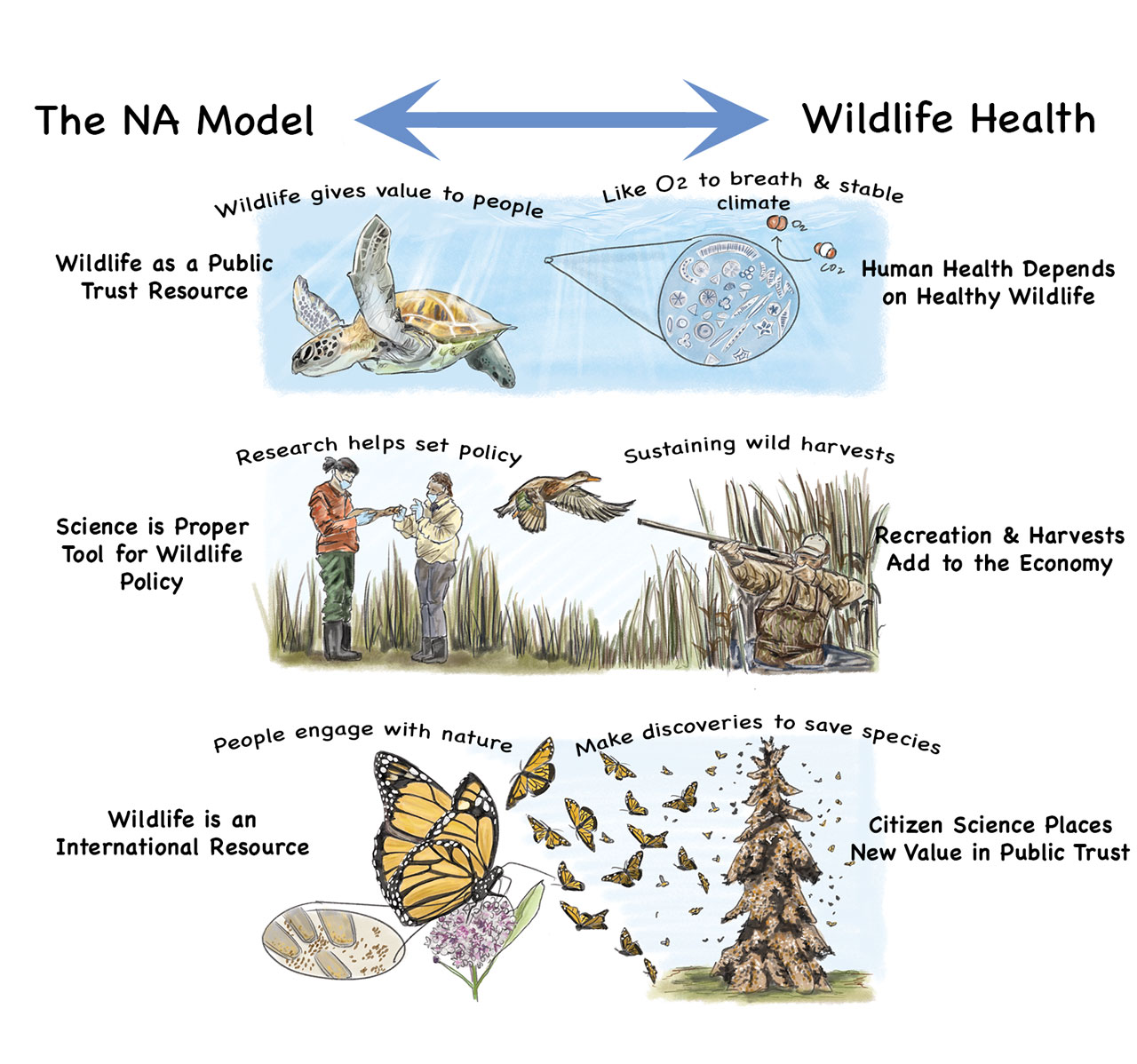

Although not formally articulated until 2001, the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation saw its beginnings with naturalist and conservationist movements of the late 1800s. It is a set of principles for the sound, sustainable management of wildlife in the United States and Canada, including the monitoring and maintenance of wildlife populations and their ecosystems. The model is the basis for legislation, research and conservation endeavors that support wildlife in North America, though it has no direct legal powers. The model was founded on seven tenets, which range from ‘wildlife as a public trust’ to ‘science is the best tool to guide wildlife policy’ and more.

The model’s two core principles are that fish and wildlife are for noncommercial use by citizens, and that they should be sustainably managed. However, experts like Radcliffe and Jessup contend that this basis in consumptive activities like hunting and fishing, while essential to millions of Americans, including indigenous peoples, misses much of what Americans value in wildlife, and therefore that the model must adapt to keep up with changing societal values.

“If we want more people to value natural resources and their protection, their views and values have to be incorporated into wildlife management and conservation policy, including traditional ‘hook and bullet’ agencies,” Jessup said. “Changing social values and politics cannot be ignored with impunity.”

Wildlife health defined

The authors set out to define wildlife health by integrating modern One Health thinking with the work of Aldo Leopold. Leopold is considered one of the fathers of wildlife ecology and is most well-known for his concept of a ‘land-ethic,’ an ethical, caring relationship between people and nature. Born in 1887, Leopold investigated ecology and conservation, informed by his roles in the U.S. Forest Service, and was a prolific educator and author until his death in 1948.

In Leopold’s work are the scientific underpinnings of wildlife health in the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, said Radcliffe. Indeed, Leopold’s concept of a land-ethic was a direct springboard for Radcliffe and Jessup’s definition of the term.

Consequently, they propose that wildlife health must comprise three core pieces: “Wildlife health is the interaction of biologic, social and environmental determinants that affect a wild animal population’s ability to cope with change (stability), recover in the face of change (self-renewal) and meet societal goals (ethic).”

This new definition offers context by demonstrating humanity’s changing relationship to nature. It highlights the importance of the land-ethic concept, and it deliberately connects health with a public trust — considered any property that belongs to the whole people.

“We know quite well that we face increasing human pressure on the planet that will affect the health of resources, so we must make sure people really know what is at stake. Personal and larger societal choices that we make now and in the next few years will determine the futures of our children and children’s children,” Jessup said. “So we must not only develop better and holistic conservation knowledge and habits, but we must also demonstrate, model and teach them.”

Focus on public trust

Radcliffe and Jessup emphasize that the model’s classification of wildlife as a public trust in particular is integral to its future, as it is a crucial way for the people to ensure that governments remain accountable for the sustainable management and health of their wild animals and wild places.

“A public trust gives value and motivates people to preserve wildlife for the next generation,” Radcliffe said. “And because health is a core part of the trust we place in nature, it necessarily bestows on all of us a responsibility to care for the earth.”

Classifying wild areas and animals as public trusts have ensured successes in the last 100 years of the model’s existence, including health benefits like clean air and clean water. The authors suggest that this may not be enough, however.

“There is no doubt that our natural resources — animals, plants and ecosystems — have never been more threatened by mankind,” Radcliffe said, noting that others have written about the failings of the model in this arena. Yet he believes that the model can work in our modern society as long as people see a vested interest in nature and embrace a responsibility for its care. This vested interest is the ‘faith’ that Leopold hoped for and outlined in his landmark work, A Sand County Almanac, which Radcliffe cites repeatedly in making the case for a public trust.

“Our proposed addendum to the model — essentially, when we take care of nature, nature takes care of us — is directly inspired by his land-ethic,” Radcliffe said. “We owe a lot to pioneering naturalists like Leopold and Theodore Roosevelt. Their vision left us with this legacy. Now we have a responsibility to carry on and uphold this idea of the public trust — one that embraces healthy wildlife as an ethic that people can have faith in — if we are to truly realize an intergenerational model of caring for wildlife and the environment.”

Written by Melanie Greaver Cordova