New horizons: Artificial intelligence in veterinary medicine

The December 2022 issue of the journal Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound was singularly focused on a hot topic in medicine — artificial intelligence (AI). The journal tapped The Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM)’s Dr. Parminder Basran, radiation oncology physicist and associate research professor and Dr. Ian Porter, veterinary radiologist and assistant clinical professor, both in the in the Department of Clinical Sciences, along with colleagues at the University of Tennessee and Colorado State University, to provide a series of review articles on the topic.

The open access articles, entitled “Artificial intelligence 101 for veterinary diagnostic imaging,” “Radiomics in veterinary medicine: Overview, methods, and applications,” and “The role of artificial intelligence in veterinary radiation oncology,” are meant to give a broad overview on the topic. “These articles provide a great starting point for anyone who wants to learn about AI and veterinary medicine,” says Basran. “While much of the focus is on diagnostic imaging, many of the articles cover topics broad enough to provide a general understanding of the AI-related subjects. They’re an accessible and readable set of articles that the community will (hopefully) enjoy.”

We had a chance to ask Basran more about AI in veterinary medicine today, and where it might take us in the future.

Q: How is AI being harnessed to help improve veterinary medicine?

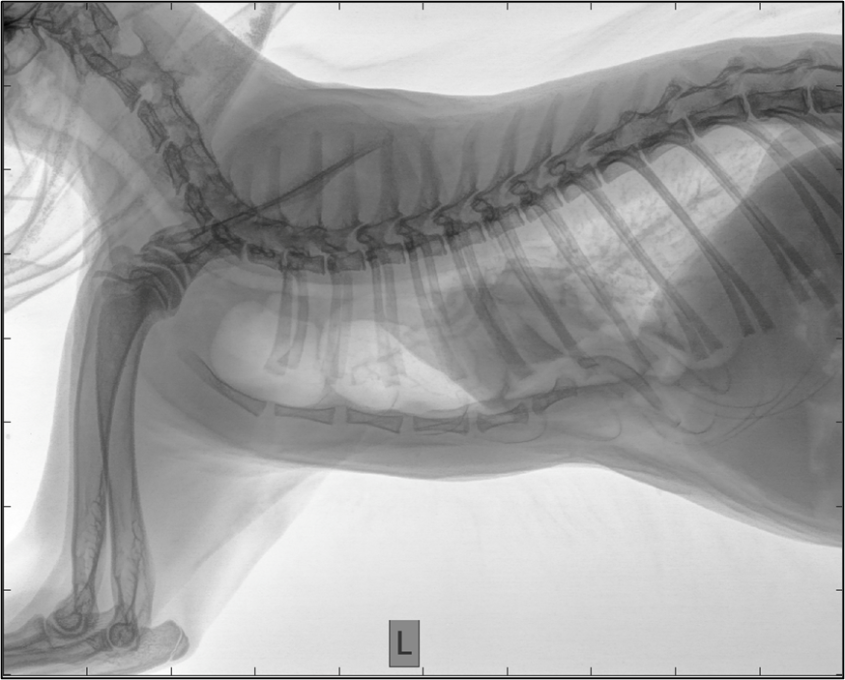

Most applications of AI in veterinary medicine are academic in nature, with a few exceptions of commercial products. Some products currently available in veterinary medicine include automated analysis of x-ray radiographs. As the pace of this technology is increasing rapidly, one can expect to see some forms of AI adopted in veterinary applications.

Q: Can you provide a specific example of how AI has dramatically changed how veterinary medicine is being done?

We have not seen AI dramatically change the practice of veterinary medicine yet, but there is a lot of potential. I firmly believe Cornell is well-positioned to lead the way in this regard.

Q: What is on the horizon for this field of work? What new breakthroughs or changes might we see in AI-assisted veterinary medicine?

AI will likely diffuse into clinical practice in small but tangible ways that could release the burden of what might be considered mundane tasks. A key example we discussed in our review paper focuses on the practice of radiation oncology. When delivering high-precision radiation treatments, it is necessary to obtain a 3D image dataset of the patient, typically with x-ray computed tomography (CT or CAT scans). The radiation oncologist then draws the tumor/target and the surrounding normal tissues on each slice of the CT scan (segmentation). This is an important but very time-consuming step, typically taking anywhere from one to four hours per patient. AI-based auto-segmentation has been explored in human medicine and can save time (30% or more) while also providing a consistent approach to segmentation (reduce inter- and intra-observer variations). Those time-savings can be re-invested into more patients accessing care or other clinical tasks.

Q: What might you say to a veterinarian who might be interested in leveraging AI in their research or clinical work, but might be intimidated or not know how to begin?

First, don’t be intimidated, especially if you have been in the profession for a long time.

Second, flip through these review articles to get a sense of what AI can bring to your practice. What we are learning in human medicine is that AI-based medicine is not a panacea but rather a tool that can alleviate burdensome tasks or reveal options you may not have considered.

Third, I think it is critical to think about the ethical and legal implications of introducing AI in the health. We need to think about how AI affects our decision making, resolve and understand biases, especially since veterinarians play a critical role in the quality of life of animals and those who care for them.

Finally, when it comes to clinical implementation, we should think of the integration of AI in clinical practice in the same way we introduce any new major technology into clinical practice. When we, for example, receive major equipment or software which can change the way we practice, we need to assemble stakeholders from all relevant disciplines, and devise a plan.

These plans should include:

a) determining priorities and selecting AI technologies carefully;

b) commissioning AI technologies where we can understand what data was used to develop models, establish benchmarks for performance with validated data;

c) introduce these technologies with solid training and education so that veterinarians understand the benefits and limitations of the technology;

d) continuously evaluate performance of the AI technologies subjected to our clinical data;

e) figure out how we might be able to improve upon these technologies by ‘retraining’ or ‘adapting’ AI algorithms based on the current standards of care and patient demographic profiles in our practices. Such a team should consist of data scientists, clinicians, administrators, and other professionals who touch AI technologies.

Q: Could AI make radiologists obsolete?

I love the quote by Dr. Curt Langlotz, Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Informatics who said: “Radiologists will not be replaced by AI. Radiologists who use and understand AI will replace radiologists who don't.”

Q: How is AI being used in human medicine today, and how far does veterinary medicine have to go to catch up?

We are seeing a LOT of new applications, ranging from Chatbots, AI-based radiology reporting, COVID-19 tracking… there are just too many to list. Veterinary medicine has a fair bit of catching up to do. A critical challenge veterinary medicine faces is that the species we treat can have so many anatomical and physiological differences (e.g., running a CT auto segmentation algorithm trained on images of Great Danes would probably perform poorly on a CT scan of Chihuahua!)

Q: What must veterinary medical institutions do to begin matching human medicine in this way?

We need tackle this challenge with training and education. Veterinarians trained in our schools today WILL be using AI technologies. We need to train future veterinarians to think about questions they should be asking when AI technologies present themselves in the clinic. We need educational courses and training for existing veterinarians so they don’t get left in the dark. This is a tough task since more we learn, the more we know, but we also learn what we DON’T know. We touch on these things in the articles.

Q: What excites you most about this field?

Cornell University is a global leader in computing science and AI development and with Weill Cornell Medicine, there are tremendous opportunities to leverage all this expertise and find novel ways in which AI can help our veterinarians work more efficiently and smarter. The Cornell University Hospital for Animals hospital has made some tremendous strides in building an exceptional data-infrastructure. This hard work is unseen but critical and establishes CVM as a gold mine of accessible and useable data. Bringing the data, scientists, and clinicians together is always a challenge, but CVM is in a great spot to lead the way globally. Personally, I love connecting with faculty and researchers from broad and diverse disciplines. CVM is an exceptional environment where veterinary AI can flourish.