Labrador’s liver repaired by minimally invasive treatment, 3D prep

When Sarah Kopa, D.V.M. ’23, adopted Kate last year, the dog was eight months old – but lacked the energy of a normal puppy. Not too long before, the black Labrador retriever had been diagnosed with a liver shunt and had to be released from her guide dog training program. To Kate’s great fortune, her new owner was not only a student at Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), but also dedicated to getting her pet the best treatment available for her condition.

Kate had a single, large-diameter, intrahepatic portosystemic shunt – a condition in which an abnormal blood vessel in the liver diverts blood away from the organ. The liver in affected pets is smaller than normal and the toxins it usually removes stay in the body, causing the animals to become sick. By the time the Kate was adopted, her condition was well managed, so she did not show some of the typical signs seen with shunts, such as seizures, gastrointestinal issues or bladder stones. “But she had low weight and stunted growth, and she would tire quickly on walks, play for short periods of time and then sleep for a while,” Kopa explained.

Kopa brought Kate to Cornell for medical management and to inquire whether the shunt could be surgically repaired. Traditionally, such a procedure is done by opening the abdomen and dissecting through the liver. Dr. Nicole Buote, associate professor in the Section of Small Animal Surgery at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals, on the other hand, offered a minimally invasive alternative. She would perform the coil embolization with a catheter inserted in a neck vessel.

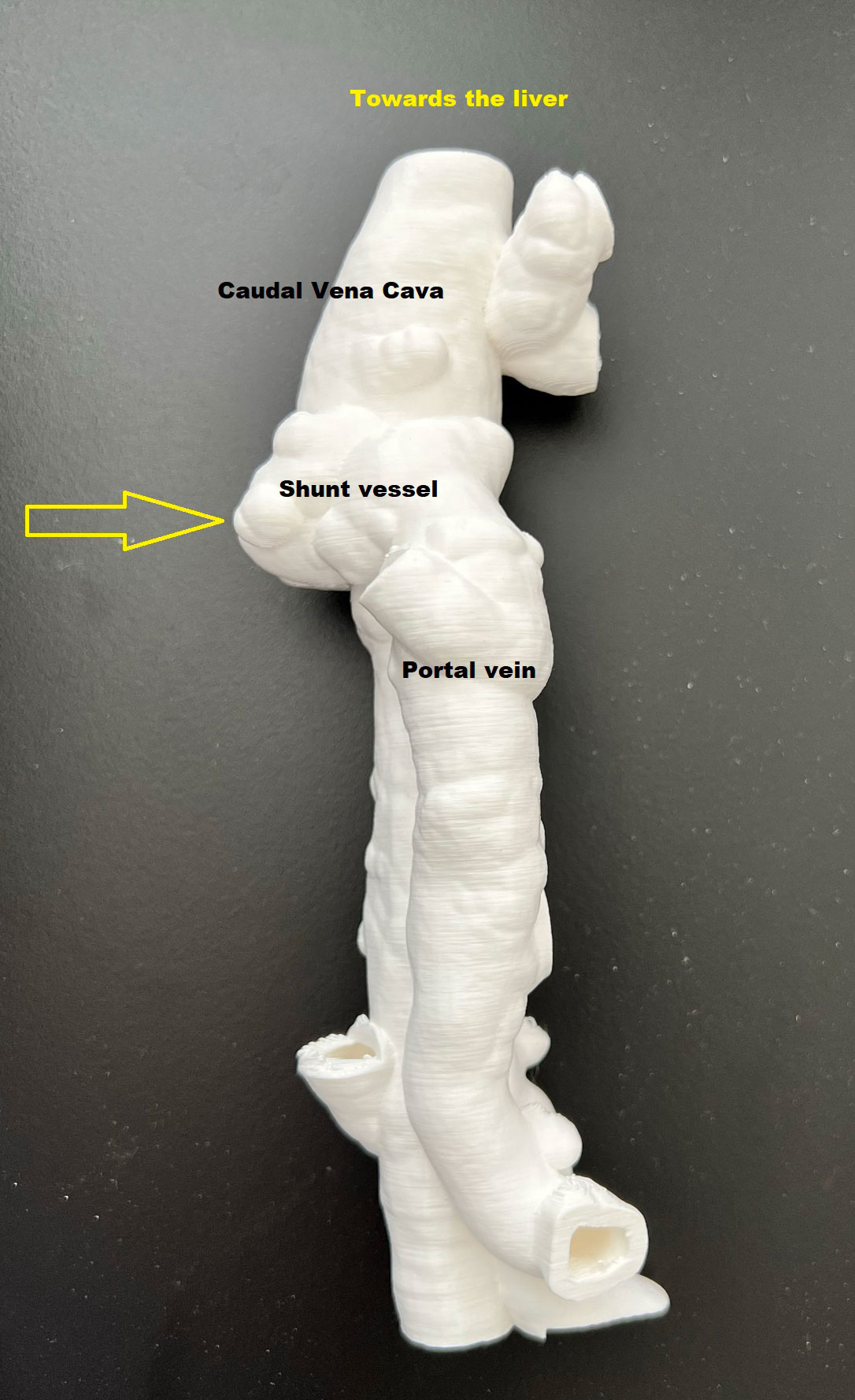

The procedure, first attempted in May, turned out to be tricky. “The condition is not very common, but I had performed this surgery before,” Buote said. “Kate, however, had a complicated shunt with a very tight turn, and it travelled right under one of the great vessels in the abdomen, the caudal vena cava.” She decided to try again a few months later – this time using 3D printing to help her prepare.

“3D printing helped us really see the anatomy we had to deal with,” Buote explained. “It has been used before in this context, though not reported in the literature.” Input from CT scans was processed by computers and turned into two different 3D prints – one by Dr. Ian Porter, assistant clinical professor in the Section of Diagnostic Imaging, and the other by third-year veterinary student Sean Bellefeuille, D.V.M. ’24, co-founder of startup company Med Dimensions.

Better visualization helped the surgical team to address Kate’s shunt by placing a catheter in a blood vessel in the neck and inserting flexible wires into the abnormal vessel and the caudal vena cava under x-ray guidance. The surgeons placed a metallic stent into the caudal vena cava and positioned special coils into the shunt, creating a blood clot and closing off the shunt to improve blood flow to the liver. “The placement went smoothly once we had the right plan, positioning and equipment,” Buote said.

During the procedure, Buote was joined by Dr. Nathan Peterson, critical care specialist and associate clinical professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences, and small animal surgery resident Colin Chik, D.V.M. ’20. Dr. John Rush, a veterinary cardiologist from Tufts University with over 15 years’ experience with such shunts, traveled in from Massachusetts to lend his expertise.

“I’m so grateful for everything Kate’s whole team did to take care of her and get us to this point,” said Kopa. “I also want to thank residents Dr. Kellie Cammarano, Dr. Alexandra Kuvaldina and Dr. Katharine Kierski, as well as all the intensive care unit techs and her amazing student doctors – Rebecca Johnson, Emma Kline, Aliyah Diamond and Julie Granger.”

Kate has recovered well, with normalized liver values and fewer medications. “She has noticeably more energy and is much more playful and excited,” said Kopa, for whom the complicated case provided exciting hands-on learning opportunities. “It was really great getting to experience most of this as a clinical year student and to have more of an understanding of how things work in the hospital,” she said. “All of Kate’s doctors have been very accessible to me whenever I had questions. It was also interesting to experience being a client at CUHA and having students report to me on her progress. As students, we give these updates every day and I learned a lot being on the other side of it.”

Buote is also very pleased with the outcome. “These shunts used to require a very invasive open surgery that had high potential for complications or death,” she said. “We got it done with amazing teamwork and in a completely minimally invasive manner – which does take a little care and research to keep finding new approaches for our loved ones. I hope this case highlights how far we’ve come in veterinary medicine over the past few decades and excites owners about what is yet to come.”

Written by Olivia M. Hall