Study points to inbreeding as a factor in Thoroughbred pregnancy losses

Experiencing the birth of a foal is an exciting event for many horse owners — but one that does not always go to plan. Some 12 to 17 percent of equine pregnancies are lost from conception through the end of gestation 11 months later.

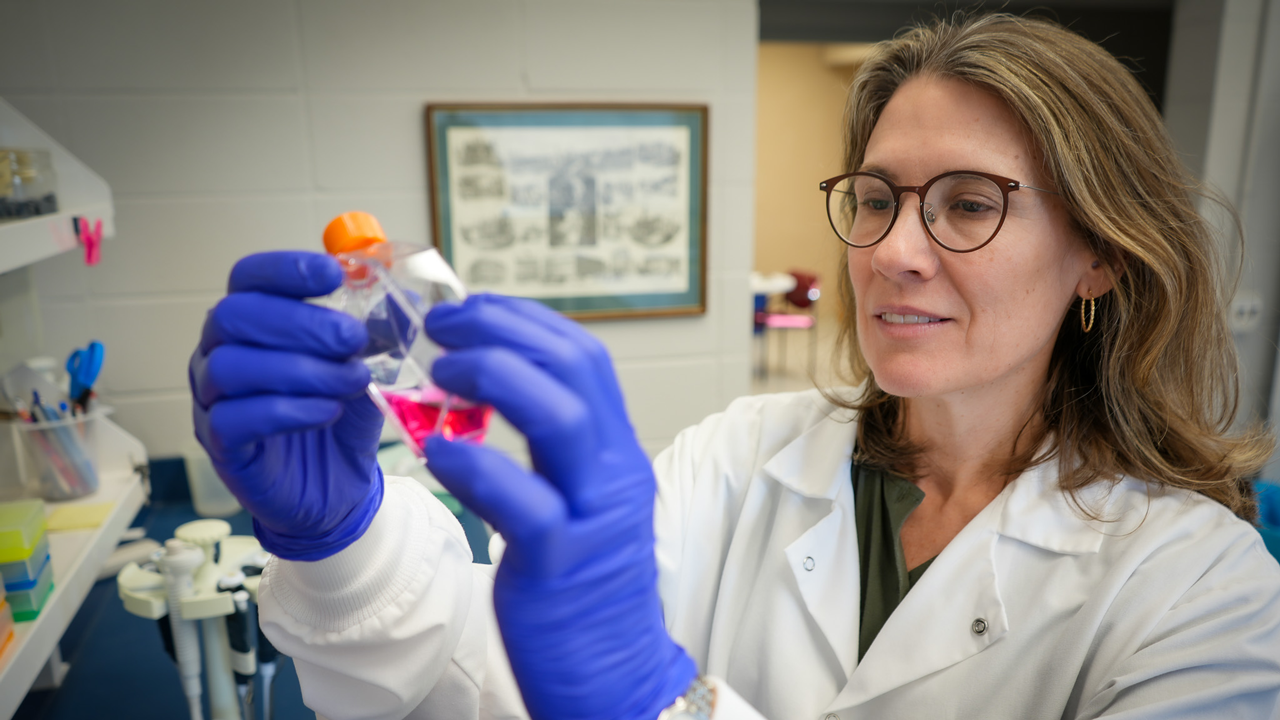

In research recently published in the Equine Veterinary Journal, Dr. Mandi de Mestre, professor at the Baker Institute for Animal Health and in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the College of Veterinary Medicine — and colleagues Dr. Jessica Lawson, research fellow at the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), University of London, and Dr. Charlotte Shilton, a previous graduate student at the RVC — set out to better understand this problem using genetic approaches.

“Pregnancy loss is one of the biggest contributors to infertility in horses, and it can be incredibly distressing for owners who are unable to produce a foal from their mare,” de Mestre said. “We wanted to know how the genetic makeup of the developing pregnancy contributes to pregnancy loss so we can develop new ways to avoid it in the future.”

Most modern horse breeds each have limited gene pools that vary between breeds. This has been shown to be associated with the accumulation of mutations that can cause various diseases that are often specific to a single breed (e.g. lavender foal syndrome of Arabians, hyperkalemic periodic paralysis of Quarter horses). In their study, the authors asked whether mating highly related Thoroughbred mares and stallions, termed inbreeding, would also be more likely to result in a compromised pregnancy.

Continuing research that de Mestre and her team had begun during her previous tenure as head of the RVC's Equine Pregnancy Laboratory, the researchers analyzed tissue samples from 131 pregnancy losses in Thoroughbreds. Samples from 58 Thoroughbred mares, representing individuals that had successfully been born, served as a control.

Using a high density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array that detects variations at 670,000 sites in equine DNA, the team looked for stretches of genetic code where an individual inherited identical genetic information from both parents, called runs of homozygosity (ROH). “If you’ve got a highly related stallion and mare, then the resulting offpring will have more ROHs,” de Mestre explained. “So we compared the number and length of ROHs between fetuses that died during pregnancy with viable adult horses, with the hypothesis being the level of inbreeding would be higher in the pregnancy loss DNA compared with control mare DNA. You could think of this as asking, ‘Is there a trigger point in current breeding practices where inbreeding is detrimental to pregnancy outcome?’ ”

Results showed that a high degree of relatedness between mares and stallions increased the chance of pregnancy loss after two months of gestation — called abortion and stillbirth. The researchers did not see any impact on early pregnancy loss, where they previously showed chromosomal problems are a more likely contributor.

Based on a previous study from France that found that Thoroughbreds have a higher level of relatedness between individuals but relatively fewer disease-causing, deleterious mutations than other breeds, de Mestre hypothesizes that loss after two months may act as a “purging event” or protective mechanism for the herd. “If you acquire an excessive load of deleterious mutations through mating of related individuals, the pregnancy fails and therefore that individual never contributes to the gene pool,” she said.

“The main take-home message for breeders is to carefully consider the level of inbreeding that may result from mating mares to related stallions,” de Mestre concluded. “It’s important to avoid mating highly related individuals, because you’re increasing the risk of the pregnancy failing in the late stages of pregnancy, which means you will lose the chance of producing a foal that season.”

The next step in research already underway in de Mestre’s lab is to figure out which deleterious mutations cause pregnancy loss. “You can then avoid breeding individuals that harbor specific mutations, rather than using the more general approach of avoiding mating of related individuals,” she said. “And hopefully in the future this could lead to new genetic tests that will guide breeding decisions.”

Written by Olivia Hall