Dr. Sean McDonough receives national award for work in forensic pathology

When Sean McDonough, associate professor in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, used to testify before grand juries in New York State in animal cruelty cases, defense attorneys would often challenge his credentials as an expert witness.

Although McDonough, an associate professor of pathology in the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), regularly conducted post-mortem exams of animals in abuse cases, he did not have certification in forensics pathology because there was no formal training offered in the field.

A decade ago, he set about changing that. “It was clear to me that we needed to develop some mechanism by which people who have the interest and the expertise could become recognized as a forensic veterinary pathologist,” he said.

McDonough formed a committee of veterinary forensic pathologists who called on the executive board of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVP) to create a fellowship in the discipline. In 2022, the ACVP launched the fellowship and McDonough became a Founding Fellow in Veterinary Forensic Pathology.

That decision came three years after McDonough created the first fellowship in forensic pathology offered at any veterinarian college in the world at Cornell. Because of his work in creating more training and recognition for the field, McDonough received the President’s Award from the ACVP in 2022.

“Dr. McDonough has been at the forefront of forensic veterinary pathology since its inception,” said Dr. Andrew Miller, an associate professor and section chief of the anatomic pathology at CVM. “He was able to build the discipline from the ground up and became an internationally recognized expert.”

A start in forensic pathology

McDonough was a veterinarian practicing in Casper, Wyoming, when he was asked to investigate his first case of animal abuse in 1982. The case involved a man who wanted to break into dog fighting and had used a puppy as bait for one of the pit bulls he was training.

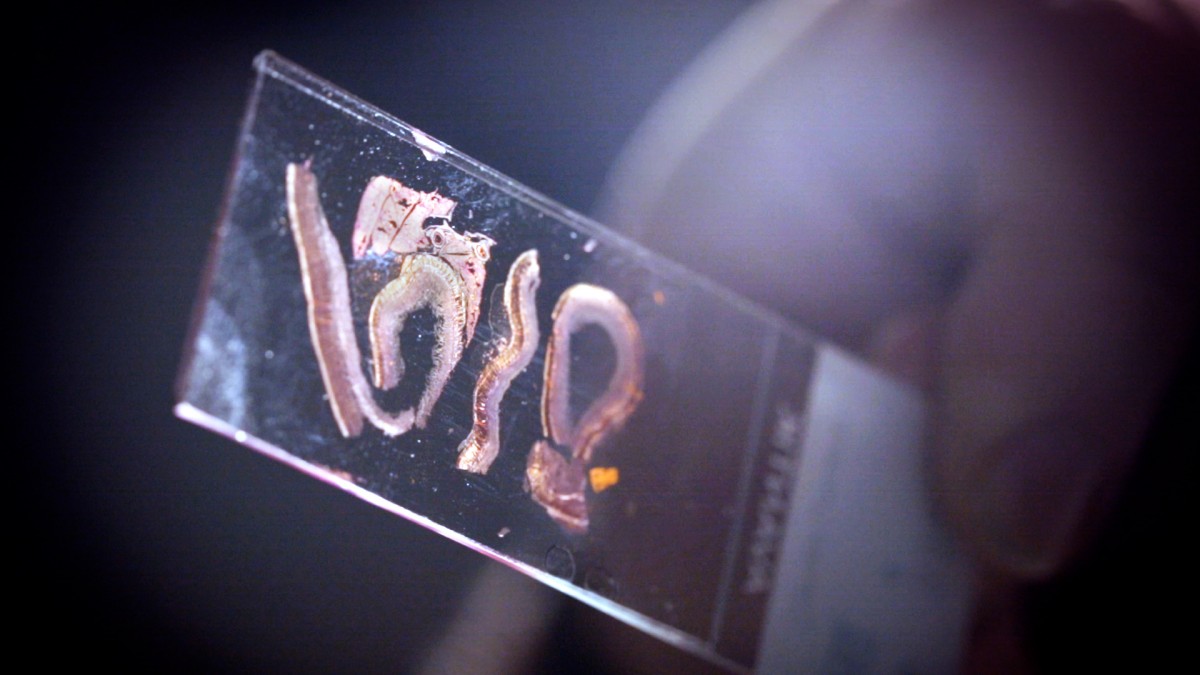

“He excited the pit bull with the puppy and then gave the puppy to the pit bull so he could bite it and kill it,” McDonough recalled. After conducting a necropsy, McDonough concluded that the puppy had died of severe bite wounds to its chest and abdomen. But because the defendant told the judge that he would never harm a puppy again, the charges were dropped.

“That was my first exposure to forensics and since I became a pathologist, I’ve been highly motivated to do my best to make sure that that never happens again,” McDonough said.

The case was a turning point for McDonough, who decided to leave veterinary practice and enter a Ph.D. program in comparative pathology at the University of California, Davis, so he could gain a better understanding of the disease process.

He hadn’t considered delving in forensic pathology until he joined the faculty at CVM in 1997. “When my department chair asked me to be head of our anatomic pathology section, I told him I would be willing to do that but we had to begin accepting forensic cases, because at that time we just weren’t taking them,” he said.

The department chair agreed, and in his first year at Cornell, McDonough handled three animal abuse cases. Not only was Cornell the only veterinary school in New York that accepted forensics cases, but it was also the only one in North America that worked on them.

“A few individuals in a few vet schools in the United States and Canada would do a few of these cases just like me — a handful a year — but there was very, very little organized activity,” he said.

Developing training in forensic pathology

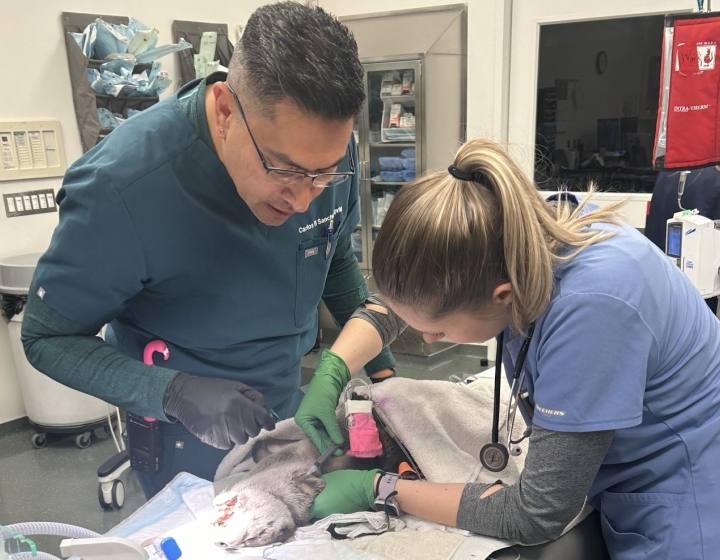

As district attorneys and humane societies became more aware of the problem of animal cruelty, the number of forensics cases CVM handled grew to about 200 annually. Instead of McDonough working on all the cases, now all eight faculty members in the anatomic pathology section do forensic post-mortem exams.

For veterinary pathologists who want to gain credentials in the field, there are now two pathways they can take: become a fellow with the ACVP through a qualifying process or complete a fellowship in forensic pathology at a veterinary school that offers one.

While CVM is still the only veterinary school that offers a fellowship in the field, McDonough notes that other veterinary schools, such as those at the University of Georgia and the University of Florida, are launching similar programs.

“I think it will be slow going,” McDonough said. “But I think that it’s an idea that is starting to catch on.”

These two types of fellowships will give veterinary forensic pathologists recognition for their expertise when they testify in animal abuse cases, McDonough said. “You wouldn’t ask the next-door neighbor to come in and speak about veterinary medicine,” he said. “The expert would be a veterinarian. Same analogy — you don’t want just anyone to come in to speak about the necropsy results. Having a veterinarian forensic pathologist address it just is best.”

Written by Sherrie Negrea

Photography by Lindsay France, Cornell University Relations