First in the field: Nigerian virologist builds lasting legacy in animal health

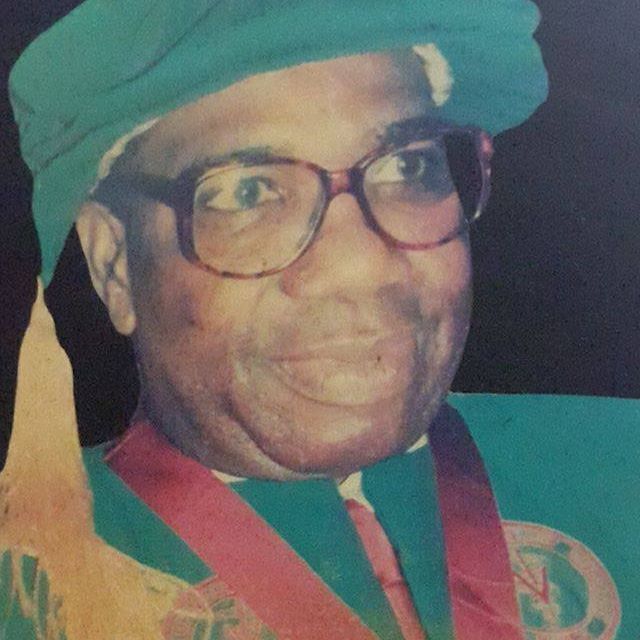

In many ways, the life of Kehinde Adesegun Abayomi Majiyagbe, M.S. ’76, Ph.D. ’79, echoed the transformations of his native Nigeria. Coming of age around the time Nigeria became independent of Britain in 1960, and subsequently studying for his doctorate of veterinary medicine during the upheaval of civil war, Majiyagbe was endlessly adaptable and dedicated to his family, country and chosen profession.

“My dad was a humble individual. It was rare that he would boast about himself,” said his son Qudus Abayomi Adesegun Majiyagbe. “People flocked to him — they wanted to learn from him. He mentored many in virology.”

“Dr. Majiyagbe contributed to strengthening the national animal health system in Nigeria, as well as within the African region,” said Dr. Caroline Yancey, director of international programs at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). “Some of the diseases he worked to control, such as African swine fever and rinderpest, affected not only animal health, but also had significant economic and food security impacts for people in the region.”

Program pioneers

As the first veterinarian from Lagos State trained in his home country, Kehinde Majiyagbe’s aptitude and skill in the work was evident early on. Born Dec. 5, 1944, Majiyagbe excelled in school, and upon graduation in 1964, explored an initial interest in becoming a science teacher. He started working with local secondary schools in Ikorodu and the Lagos Island Local Government areas — but his life took a sharp turn both personally and professionally within a year. His father had passed away when Majiyagbe was a young child, and in 1965, he lost his mother as well. His professional aspirations pivoted that same year, with Majiyagbe being recruited to a pilot program to study veterinary medicine.

“Prior to 1965, if you wanted to study veterinary medicine or human medicine, you had to go overseas,” Qudus Majiyagbe said. “My dad therefore became part of the first crop of Nigerian-trained veterinarians.”

This pilot program was the first of its kind in Nigeria. A partnership between the University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria and Ahmadu Bello University, Zaira, Kaduna State, the program recruited talented individuals from across the country to study for their doctorate of veterinary medicine and thereby establish a number of trained professionals for the young country. The program was modeled after the veterinary curriculum of Kansas State University at the time, featuring both pre-clinical and clinical components. In 1970, Kehinde Majiyagbe and his groundbreaking cohort graduated, and he quickly joined other veterinarians, scientists, technologists and animal scientists at the National Veterinary Research Institute in Vom, Plateau State, Nigeria.

“Reflecting back on that first class, although some of them have passed away, they all distinguished themselves in different fields of veterinary medicine in Nigeria,” Qudus Majiyagbe said.

International adventure

Indeed, it didn’t take long for Kehinde Majiyagbe to make strides in veterinary medicine himself. He pursued his passion for immunology and virology, earning a federal government postgraduate scholarship that sent him across the world to Cornell in 1973.

The scholarship was part of a concerted effort by the government of Nigeria following the end of its civil war, said Qudus Majiyagbe. “The scholarships were a way of Nigeria showing some form of reconciliation among its people. This is 10-15 years of us transitioning from a British colony to our own nation showing that we are competent and can stand with the rest of the world.”

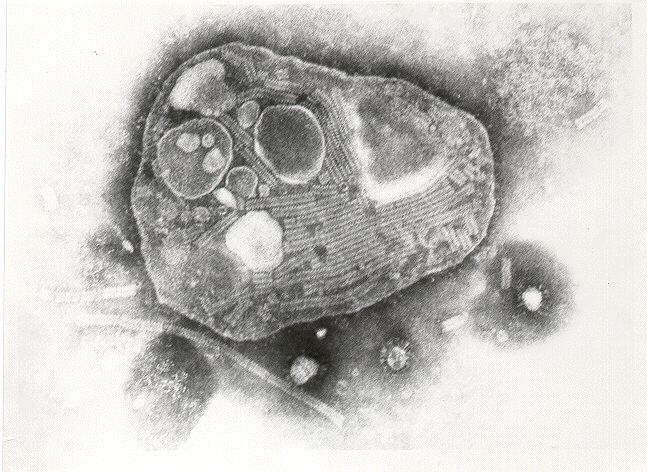

Kehinde Majiyagbe didn’t embark on this international adventure alone. His wife, Atinuke Nihinlola Dosunmu Majiyagbe, and their son, Babajide Olalekan Majiyagbe, accompanied him to upstate New York and CVM. There, Kehinde Majiyagbe earned his master’s of science in immunology in 1975 with the thesis “Extraction and Purification of Equine Infectious Anemia Virus Antigen,” advised by Leroy Coggins, Ph.D. ’62, and Dr. Neil Norcross. His Ph.D. in virology, “Studies on African Swine Fever Virus: Host Cell-Virus Interactions,” followed in 1979, with committee members Leland Carmichael, Ph.D. ’59, the John M. Olin Professor of Virology; Dr. Gary Cockrel; Dr. Stephen Hitchner; and Norcross.

Qudus Majiyagbe himself was born in Ithaca, and spent the first few years of his life there. “There were other international families there at the time, and we were able to keep in touch even after returning to Nigeria,” he said. “My mom talks about our life at Cornell as being quite nice — she was also studying at Tompkins County Community College at the time.”

“Having matriculated international students in the college is mutually beneficial. These students can take back new knowledge, skills and a network of colleagues, and to the college they bring diversity, new ideas and new experiences,” Yancey said. Learning and working alongside students from different backgrounds, cultures and perspectives broadens our understanding of the world, and builds cultural sensitivity and cultural competence, she adds. “It contributes to innovation and creativity. If we want to develop the next generation of leaders that can solve complex global animal health issues, we need to foster these qualities of collaboration, cultural competence and innovation in our students.”

Even before completing his dissertation, Kehinde Majiyagbe’s immunology expertise earned him a position at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center, a government research facility on Long Island, where he studied foot and mouth disease and investigated the African swine fever virus outbreak happening in Cuba at the time. The facility’s primary goal was to safeguard American livestock from diseases, but it had a history of conducting work as varied as veterinary vaccine stockpile contributions and a secret bioweapons program during the Cold War.

Majiyagbe honed his skills at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center for several years before returning with his family to Nigeria in 1979. Here, Majiyagbe rejoined his former employer, the National Veterinary Research Institute (NVRI) in Vom — and made use of his professional adaptability during 37 years of service.

“Dr. Majiyagbe provides a great example of the exponential impact one CVM student can have after graduation,” Yancey said.

Leading the way

Back at NVRI, Majiyagbe took on the role of principal veterinary research officer. This would be the first step in his path as an immunology leader and mentor. He held various positions during his long career at NVRI, including terms as director of several different sections and head of its diagnostic and research laboratory.

At NVRI, Majiyagbe responded to several zoonotic disease outbreaks, some with devastating economic impacts. Among the first was the highly infectious and fatal rinderpest disease. In the 1980s, an outbreak in Africa killed millions of cattle and some wildlife. Thanks in large part to contributions from NVRI and international collaborations on vaccination and disease surveillance, rinderpest was largely purged from the African continent by the 1990s.

“The NVRI helped lead the vaccination program for rinderpest, and that coordination became very helpful when we first encountered avian influenza,” Qudus Majiyagbe said.

“Rinderpest was a hugely impactful animal disease globally. It was economically devasting and affected food security, including contributing to hunger and famine in some regions,” Yancey said. In 2011, it was declared eradicated by the World Organization for Animal Health. Only one other infectious disease has been eliminated globally — smallpox for humans. Said Yancey, “The eradication of rinderpest was a major achievement for the veterinary profession, and it was possible due to international collaboration, and by the contributions of knowledgeable and committed veterinarians such as Dr. Majiyagbe.”

Kehinde Majiyagbe’s presence at NVRI ensured that national and international collaborations took place, securing partnerships between NVRI and international universities and organizations. “Animal infectious diseases do not know geographical boundaries and we need veterinarians that can collaborate across disciplines and cultures to prevent disease spread and improve animal health,” Yancey said.

This was a position in which Majiyagbe excelled, though he was sometimes stymied by events out of his control. For example, when African swine fever struck Nigeria in the early 2000s, not only was he the go-to subject expert, but he attempted to forge a partnership with his former colleagues at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center, who had dealt with a similar outbreak during his tenure there. However, the center’s oversight had recently transferred from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to the Department of Homeland Security. This was a direct result of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which also inspired new rules that prevented such a collaboration.

Qudus Majiyagbe was studying at the University of Houston-Downtown in Texas at the time. “I remember writing in support of my father and this collaboration, but nothing came from it,” he said.

Government praise

Government officials lauded Kehinde Majiyagbe’s efforts to safeguard Nigerian veterinary medicine and industry. He was recruited by the Nigerian Ministry of Agriculture to be its chief technical officer for the Food and Agriculture Organization and the Nigerian government’s National Special Foods Security Program. Majiyagbe used the program for capacity building, often arranging for staff to visit other countries to see how they managed trans-boundary and zoonotic diseases.

These government and international agency partnerships continued to fulfill his original mission of adding to veterinary immunology expertise in Nigeria so many years ago. Groups he worked with, either through NVRI or the government, included the African Union, the European Union, the World Bank, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the World Organization for Animal Health, the Food and Agriculture Organization and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, among others.

Even at the time of his retirement from NVRI in 2007, Majiyagbe joined the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and the Federal Ministry of Health in their response to an outbreak of the highly transmissible avian influenza, contributing his decades of experience to help contain the virus.

A foray into business

The list of Majiyagbe’s achievements in the organized veterinary realm is long — editor in chief for the Nigerian Veterinary Medical Association; a Foundation Fellow, founding member and the first college secretary of the Nigerian College of Veterinary Surgeons, to name a few — but upon his retirement from NVRI in 2007, Majiyagbe switched gears and joined his son Qudus Majiyagbe as a consultant for the latter’s business.

Qudus Majiyagbe’s degree in applied microbiology from the University of Houston-Downtown led him to work in human medical research at the Baylor College of Medicine and with biotech and pharmaceutical manufacturing companies. After earning his master’s in business administration, he started a consulting agency for human and animal medicine partners. He coordinated the biotechnology and pharmaceutical end of the business, and his father consulted on the animal health and production end, until Kehinde Majiyagbe’s passing in 2017. Qudus Majiyagbe described his dad as his biggest mentor, and said he isn’t the only one who feels that way. For years, Kehinde Majiyagbe taught veterinary microbiology part time at Ahmadu Bello University and the University of Ibadan, and went full time after retirement. He not only served on advisory panels for Ph.D. candidates, but also had a hand in the formation of exams for D.V.M. students. He made a point of motivating people in his lab to pursue their Ph.D., Qudus Majiyagbe added. “I think he probably learned that at Cornell, that encouragement to continue your schooling.”

“Dr. Majiyagbe also researched infectious diseases throughout his career, advancing the understanding of these diseases and their control in Nigeria, and shared his knowledge through teaching and mentoring veterinary students,” Yancey said. “And the collaborations and international partnerships that he worked to develop can have long-lasting impacts.”

After his death in 2017, Kehinde Majiyagbe is remembered by his family and friends as a dedicated Christian and lover of jazz music. He loved traveling and to play squash, and was dedicated to his family and the veterinary community.

“I saw my dad’s dedication to veterinary medicine from a young age,” Qudus Majiyagbe said. “I remember he would go into the field for samples, check on disease spread or dispense vaccines — he’d leave wearing a white shirt and come home in something dirty and brown. He worked very hard.”

His impact on the people around him is rivaled only by his impact on the field.

Said Yancey, “As Dr. Majiyagbe demonstrates, international graduates that contribute to research, education and veterinary organizations can elevate the veterinary profession globally.”

Written by Melanie Greaver Cordova