Rapid Response Fund takes aim at emergent threats to feline health

Bird flu is on the move—spreading among wild birds, poultry, dairy cows and, occasionally, humans. As cases in cats rise, the Cornell Feline Health Center (FHC) has mobilized its Rapid Response Fund (RRF), awarding nearly $400,000 to establish the Cornell Feline Health Center Feline H5N1 Consortium, a team of Cornell researchers focused on investigating the virus’ spread and impact on the species.

The grant is the latest of over a dozen supporting urgent, high-impact research on emerging threats to feline health that cannot await submission through the annual Cornell Feline Health Center grants program, which has provided over $7,000,000 in funding to feline -focused Cornell researchers in the past 25 years. Since its inception in 2012, the RRF has disbursed nearly $1,000,000 to Cornell researchers investigating emergent threats to cats. “This is all made possible by the kindness of our donors,” said FHC director Bruce Kornreich, D.V.M. ’92, Ph.D. ’05.

Closing the funding gap

The idea for the Rapid Response Fund emerged in 2012, when the newly identified feline morbillivirus in Hong Kong raised concerns that it might be contributing to chronic kidney disease in cats. John Parker, Ph.D. ’99, associate professor of virology at the Baker Institute for Animal Health and in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and Dr. Edward Dubovi, professor in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, launched a surveillance study to determine whether the virus was present in the U.S. cat population. It wasn’t.

“But this got us thinking,” said Kornreich. This emerging problem came between grant cycles, in which a year or more can pass between application and funding. “What could we do to quickly improve our ability to diagnose, treat, and prevent disease?”

The Rapid Response Fund was designed to close that gap. A streamlined review process enables researchers to access funding within weeks — ideal for fast-moving infectious diseases. “I believe it makes us unique,” said Kornreich. “I’m not aware of any other feline-focused institute that provides a similar funding mechanism.”

Rising to meet COVID-19

Support from the fund has grown significantly in recent years, driven largely by urgent needs related to SARS-CoV-2 — the virus behind the COVID-19 pandemic — and feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a highly impactful disease of cats that was untreatable and almost routinely fatal until the development of effective treatments beginning in 2018.

When COVID-19 struck in 2020, Dr. Diego Diel, professor of virology in the department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences and director of the Virology Laboratory at the Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center (AHDC), used RRF funding to study the risk SARS-CoV-2 poses to cats and to develop diagnostic testing tools. His team created two assays: one that detects the virus directly in tissues, and another that identifies antibodies signaling prior infection. The antibody test is now a routine service at the AHDC and has been used to confirm SARS-CoV-2 infections in Bronx Zoo lions and tigers, screen cats before spay procedures at Cornell, and monitor immune responses in animals after vaccination.

In 2021, Diel’s group received a follow-up grant to study a severe COVID-19 case in a domestic cat. They discovered the cat had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a heart condition linked to worse outcomes in both cats and humans. “Without rapid response funding, this work would have taken place much later,” Diel said.

Staying ahead of feline coronavirus

Just a few years later, Diel’s FHC colleagues faced another coronavirus challenge—this time a feline-specific threat. Dr. Gary Whittaker, the James Law Professor of Virology in the departments of Microbiology and Immunology and of Public and Ecosystem Health, has long studied feline coronavirus (FCoV-1) and how some strains mutate into the deadly FIP. “That virus is endemic and can be assessed on a typical yearly grant funding cycle,” he said.

But in 2023, a new strain of a different FIP-causing feline coronavirus (FCoV-2) suddenly emerged in Cyprus, causing widespread disease and high mortality in the local cat population—an outbreak Whittaker helped characterize as part of a consortium of researchers. Supported by a rapid response grant, he enlisted the help of Laura Goodman, Ph.D. ’07, assistant professor at the Baker Institute for Animal Health and in the Department of Public and Ecosystem Health, to run genomic surveillance for FCoV-2 on free-ranging cats in New York City.

“People bring pets from overseas, and they can carry infectious diseases,” Goodman said. “We’re closely monitoring for this variant with partners at Columbia University, the New York City Health Department, and local vets.” Her lab has developed a website to share surveillance data with clinicians, shelters, and others interested.

Ready to take on avian flu

With this experience, Whittaker believes the FHC has the experts and infrastructure to confront the growing threat of avian influenza in cats. “We’re perfectly positioned to be the leader in the nation, if not the world, for tackling this problem,” he said. “I don’t think it’s on anyone else’s radar in terms of an actual response.”

The latest round of rapid response funding supports a multi-lab collaboration spearheaded by Whittaker that will focus on monitoring the virus’s spread in felines. Initiated by Dr. Lena DeTar, associate clinical professor of shelter medicine in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, she and her team will gather samples from cats across a range of settings — shelters, homes, and the outdoors. “We need to return to epidemiology and see what’s really out there and what the risk is,” Whittaker said.

That risk appears real: a recent study by the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab found that 25 percent of tested bobcats in New York state were infected with H5N1.

Once the samples have been collected, the Goodman lab will run genomic surveillance for active infections and the Diel team in the ADHC will look for antibodies for bird flu to assess past exposure. In fact, Goodman had already been thinking about influenza even before the latest outbreaks. In 2023, she was wrapping up a project funded by the FHC on pathogens in raw cat food when cases of avian influenza in cats linked to contaminated food were reported in Poland and South Korea. A rapid response extension of the original grant allowed her to analyze the samples purchased between 2021 and 2023. None tested positive.

But in 2024, as cats in the United States began dying of bird flu, cat food became a suspected source. “The cases in the news are probably just the tip of the iceberg,” Goodman said. “We need to monitor not just food but also healthy cats to detect possible asymptomatic infections.” That’s particularly important, she noted, because industry-wide standards for testing and processing food to inactivate avian influenza virus don’t yet exist. “Everything is reactionary right now. There are probably a lot more contaminated products than we know about.”

Predicting risk at the molecular level

Whittaker and his team are building on insights from their work with FIP to develop a risk-assessment protocol for influenza based upon the virus’ molecular structure. Doctoral student Alivia Ishee is collaborating with researchers in the lab of Harel Weinstein, the Maxwell M. Upson Professor of Physiology and Biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, to computationally predict viral structures by their genetic sequences. Using structural bioinformatics and machine learning, the team aims to move beyond raw genetic data to assess risk based on viral hemagglutinin (HA) protein, which plays a critical role in viral entry and infectivity.

“We’re pushing the boundaries of our knowledge to try to build in this structure-based risk assessment tool versus a sequence-based tool,” he said. “Such tools, when combined with information of co-factors in the host, can help us assess whether particular strains are evolving that would predict increased pathogenesis and spread.”

The Whittaker lab will also carry out experiments using cultured feline cells to test a range of anti-viral drugs as a first step toward identifying the most effective treatments for H5N1 infections in cats and potentially in other species. These experiments will also help identify strains of the virus that may be developing drug resistance, an important consideration in establishing safe therapies for H5N1 infections.

Launchpad for discovery

The researchers hope to sustain these efforts beyond the period of the rapid response grant. “We can’t just sample once and walk away,” Whittaker said. Collecting sufficient data will help the scientists to secure additional collaborations and external grants — something they’ve done repeatedly in the past. For example, Whittaker’s work on FCoV-23 led to an upcoming Nature paper with colleagues at the University of Washington, while Diel secured NIH and USDA grants to study SARS-CoV-2 in cats, building on preliminary data generated with support from FHC.

This unique combination of rapid response funding and external grants has kept FHC and the investigators it supports at the cutting edge of feline health research. “The ability to be nimble with a rapid response has to come from a secure foundation,” Whittaker said, likening the model to NIH Centers of Excellence. “The Feline Health Center has the infrastructure — equipment, expertise, and people who work well together — that allows for the necessary speed as well as accountability.”

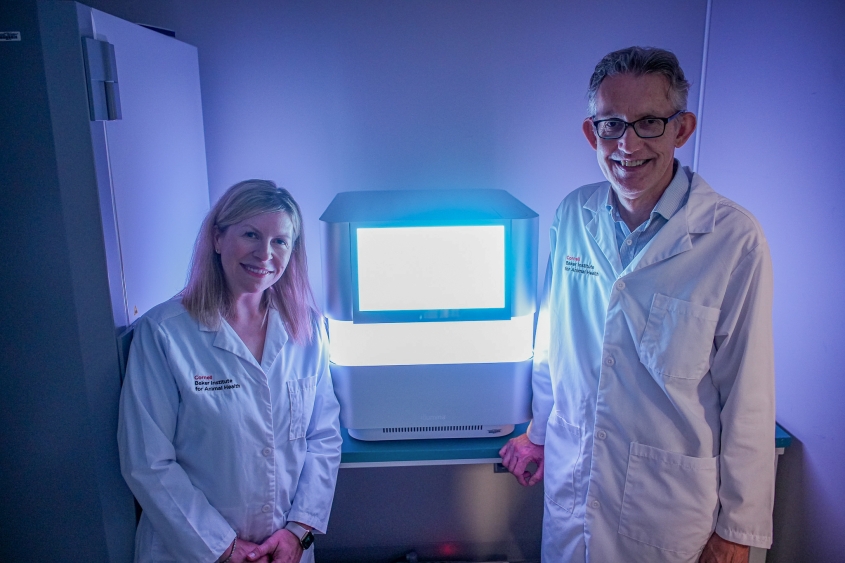

A recent FHC RRF investment in a newest-generation NextSeq 1000 sequencer illustrates that dual mission by supporting urgent investigations like the current avian flu work while building long-term capacity for viral surveillance. Given federal funding uncertainties, this flexibility is vital, Diel said. “FHC’s Rapid Response Fund and other grants will be even more critical to maintaining the high-quality research Cornell is known for.”

Article written by Olivia M. Hall