Research

Are raw cat foods safe?

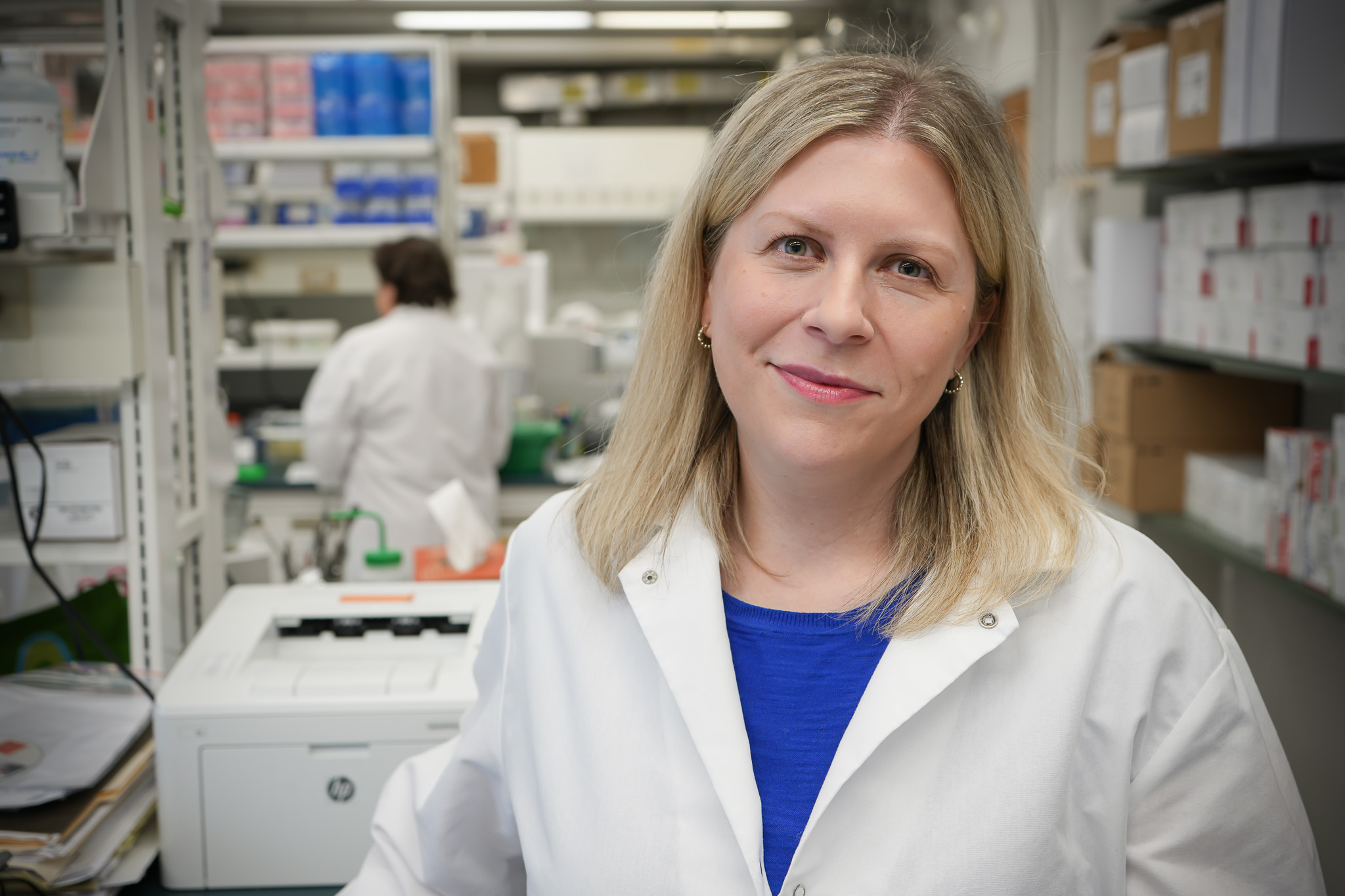

Loving pet owners want only the best for their animals, and a growing number of pet food companies are telling consumers that raw food is exactly what cats and dogs need to thrive like their tiger or wolf ancestors. But an ongoing study by Laura Goodman, Ph.D. ’07, assistant professor in the Department of Public and Ecosystem Health and with the Baker Institute for Animal Health, is quantifying the risks of some of these diets.

“The increased exposure to bacteria and parasites that are pathogenic to animals and humans is the main concern,” Goodman explained. “Dogs and cats eating raw diets can shed pathogens without showing any signs of clinical illness, which puts the whole household at risk, especially young children.” Indeed, manufacturers have been forced to recall a number of raw pet foods due to bacterial contamination, for example after a kitten died in 2018. A report from the United Kingdom a year later also found an association between infections with Mycobacterium bovis (a member of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex) in cats – some of them fatal – and raw food diets.

Given the risk of illness associated with certain “wild” pet foods, major institutions such as the American Veterinary Medical Association, the FDA, the CDC as well as the Cornell Feline Health Center (CFHC) advise against feeding them to animals. “We feel that it’s an unnecessary risk because there's really no demonstrated benefit we’re aware of in feeding these raw foods compared to cooked foods,” said CFHC director Bruce Kornreich, D.V.M. ’92, Ph.D. ’05.

Nevertheless, many raw products are available at major retailers, especially online, and by direct order through manufacturer websites. Their popularity is especially growing across the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. “The industry is marketing these foods as closer to what animals ate in the wild,” Goodman said, explaining that they are thereby tapping into concerns people may have about overly processed foods with many additives. “Social media is a big factor,” she said. “This falls under the bigger problem of scientific mistrust and spread of misinformation online. Much like how there are celebrity doctors who endorse disproven claims about human health, there are veterinarians who promote raw diets.”

Goodman – who previously worked in veterinary diagnostics and was involved in testing samples from sick animals that ate raw food – hopes to provide additional scientific grounding to the discussion by using cutting-edge, deep DNA sequencing technology to screen a broad range of commercially available raw foods for the presence of harmful pathogens. Funded exclusively by CFHC in mid-2020 as part of a special call for projects on feline natural nutrition, Goodman will have bought and tested 150 samples by the end of the project in June 2023. (Her lab also receives support from the FDA to help maintain its capacity for bacterial genome sequencing.)

The study’s samples will cover the breadth of different “raw” food types. Unlike conventional pet food – which is ground to a size appropriate for thorough cooking and then shaped and dried or poured into cans and steam sterilized – raw food is not subjected to heat treatment. Instead, manufacturers try to reduce the amount of harmful bacteria on the outside of animal-based ingredients with chemical treatments such as acid washes before they are mixed with grains or vegetables. “Fresh” pet food is partially cooked and therefore a bit safer, but it still requires special care (storage in the refrigerator and careful washing and sanitizing of bowls).

Raw ingredients may also be found in freeze-dried food, often meat-based treats or toppers. “As a pet owner, I know that freeze-dried treats are very popular, and I was surprised that so many of them are raw,” Goodman said. “It’s important to know if the product you are purchasing was cooked prior to freeze-drying, because this process preserves harmful bacteria such as Salmonella and keeps them alive nicely.” Such freeze-dried raw meat also surrounds “raw-coated” kibble.

With the help of M.P.H. student Aaron Malkowski and postdoctoral researcher Dr. Guillaume Reboul, Goodman is using established methods to culture Salmonella and other Gram-negative bacteria (characterized by strong walls that contribute to antibiotic resistance). The researchers soak and blend the food before mixing it with a series of different enrichment broths, which get incubated at specific temperatures and examined for colony growths in Petri dishes. “Whenever Aaron grows something interesting, we can all tell because the lab smells awful,” Goodman reported.

A technique called “molecular barcoding” allows the researchers to identify bacterial species and look at the animal sources of the food to confirm that they match what is on the labels. “We are purifying DNA from the original food material to essentially look at the complete microbiome of that food product, including possible pathogens, and the mitochondrial DNA of the original animal meat sources,” Goodman explained.

What distinguishes this study from the biggest report to date – conducted by the FDA via six independent labs testing over 1,000 samples of dog and cat food and published in 2014 – is that Goodman is focusing on feline food, casting a wider net for different bacteria, and examining if different animal sources are associated with specific bacterial pathogens. “Dr. Goodman's work is really cutting-edge,” Kornreich said. “Consistent with other projects that we are able to fund – thanks to our donors – it’s innovative, important, and potentially highly impactful on an issue that’s controversial among cat owners and veterinary professionals alike.”

Thus far, the researchers have 68 different bacterial isolates undergoing further characterization. All stemmed from the raw food samples (45 wet, 18 freeze-dried, 5 raw-coated kibble), while none of the conventional products produced any cultures. Among the bacteria they have found are Salmonella, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Cronobacter sakazakii, Morganella morganii, Providencia alcalifaciens, and E. coli.

Salmonella harbored in two of the frozen raw wet food products share a very close genetic relationship with at least one human salmonellosis case in the public database Goodman uses for comparison of her isolates with those collected by federal surveillance programs. “The Cronobacter finding on raw-coated kibble was concerning, as this was at the same time that powdered infant formula was being recalled due to the same bacterial agent,” Goodman said. “The food contaminated with Cronobacter also had over 100 different antibiotic resistance genes detected. The presence of these genes in food or the environment is a risk because they can get transferred between different strains and even scavenged from dead bacteria.”

Goodman plans to publish this work in a peer-reviewed scientific journal in the future and meanwhile is adding samples from the study to the federal pathogen database in real time. “Although we are keeping the manufacturers’ names out of any publication, if any future isolates from pets or people match these from our study, it will be evident that there is a match to a pet food product,” she said.

For pet owners who still want to feed their pets as naturally as possible – but safely – Goodman has the following advice: “Although there is no legal definition of ‘natural,’ it typically means the absence of artificial ingredients,” she said. “There are plenty of great manufacturers that make nutritionally complete meals that are safely cooked and labeled as natural. Make sure there are no raw components on the labeling and look for detailed information on their website about their quality and safety program. Finally, trust your own veterinarian for advice."

Article written by Olivia M. Hall

Recent data available on growth of the raw food segment, and the percentage of pet owners feeding raw food.