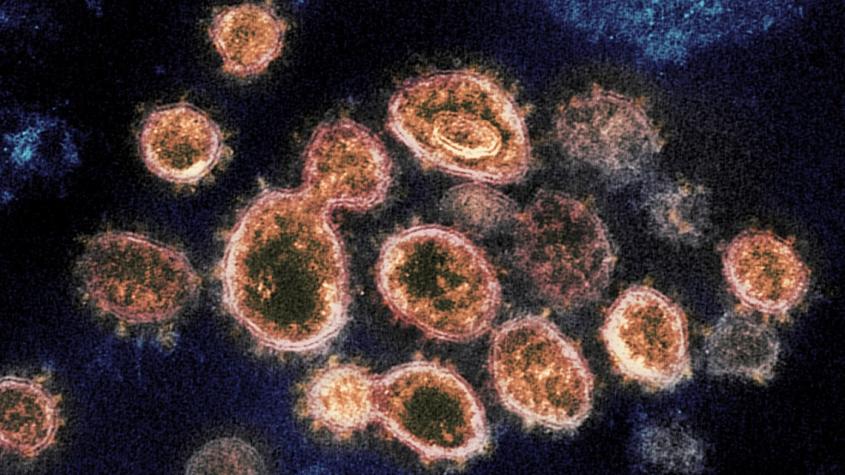

Structure of COVID-19 virus hints at key to high infection rate

A Cornell study of the structure of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, reveals a unique feature that could explain why it is so transmissible between people. The Cornell group also notes that – aside from primates – cats, ferrets and mink are the animal species apparently most susceptible to the human virus.

Gary Whittaker, professor of virology in the College of Veterinary Medicine, is senior author of “Phylogenetic Analysis and Structural Modeling of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Reveals an Evolutionary Distinct and Proteolytically Sensitive Activation Loop,” which published April 19 in the Journal of Molecular Biology.

The study identifies a structural loop in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, the area of the virus that facilitates entry into a cell, and a sequence of four amino acids in this loop that is different from other known human coronaviruses in this viral lineage.

An analysis of the lineage of SARS-CoV-2 showed it shares properties of the closely related SARS-CoV-1, which first appeared in humans in 2003 and is lethal but not highly contagious, and HCoV-HKU1, a highly transmissible but relatively benign human coronavirus. SARS-CoV-2 is both highly transmissible and lethal.

“It’s got this strange combination of both properties,” Whittaker said, noting the researchers are focused on further study of this structural loop and the sequence of four amino acids. “The prediction is that that loop is very important to transmissibility or stability, or both.”

Other recent research has identified a bat in China that carried a coronavirus with a similar loop but a different sequence of amino acids, which adds another lead for future inquiry, Whittaker said.

The researchers also compared the SARS-CoV-2 structural model with those of coronaviruses found in other animals and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 originated in bats. It had been suggested that the virus may have passed through pangolins (a scaly anteater), but comparisons of viral sequences and structures found no evidence of that, according to the study.

“How [SARS-CoV-2] got into humans is still unclear,” Whittaker said.

A newly identified genetic sequence in SARS-CoV-2 points to the possibility of an unknown intermediate host, he said.

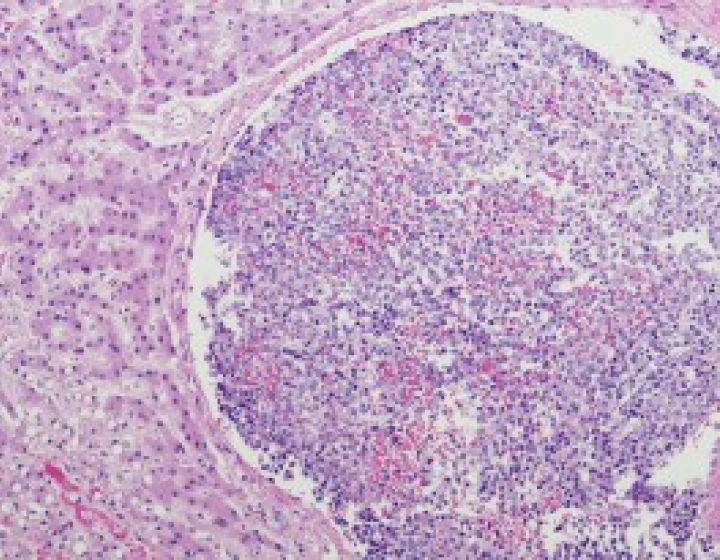

Cats, ferrets and minks are also susceptible: In order to infect a cell, features of the spike protein must bind with a receptor on the host cell’s surface, and cats have a receptor binding site that closely matches that of humans. To date, infections in cats appear to be mild and infrequent, and there is no evidence that cats can, in turn, infect humans.

Whittaker added that investigations into feline coronaviruses could provide further clues into SARS-CoV-2, and coronaviruses in general.

“We are keeping an open mind to see if similar things may happen in cats that already that are now happening in humans,” he said.

Javier James, a postdoctoral researcher in Whittaker’s lab, is the study’s first author. The work is supported by the National Institutes of Health.

By Krishna Ramanujan