Catching up to human treatments for canine AML

Losing a dog to cancer is always devastating, but losing one to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an especially heart-wrenching experience because it happens so fast. Dr. Kelly Hume, an associate professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences and veterinary oncologist at the Cornell University Companion Animal Hospital, recalls a recent case where a three-year-old large-breed dog lived just 19 days after the initial diagnosis, despite supportive care and two different types of chemotherapy.

Some dogs are too sick at diagnosis even to attempt treatment, but for others, the standard therapy may give them a few more months. "One of the challenges with cancer treatment is that it's such a roll of the dice," said Hume. "That's why research is so important — so that we can have better treatment guidelines and give owners more accurate expectations for the future."

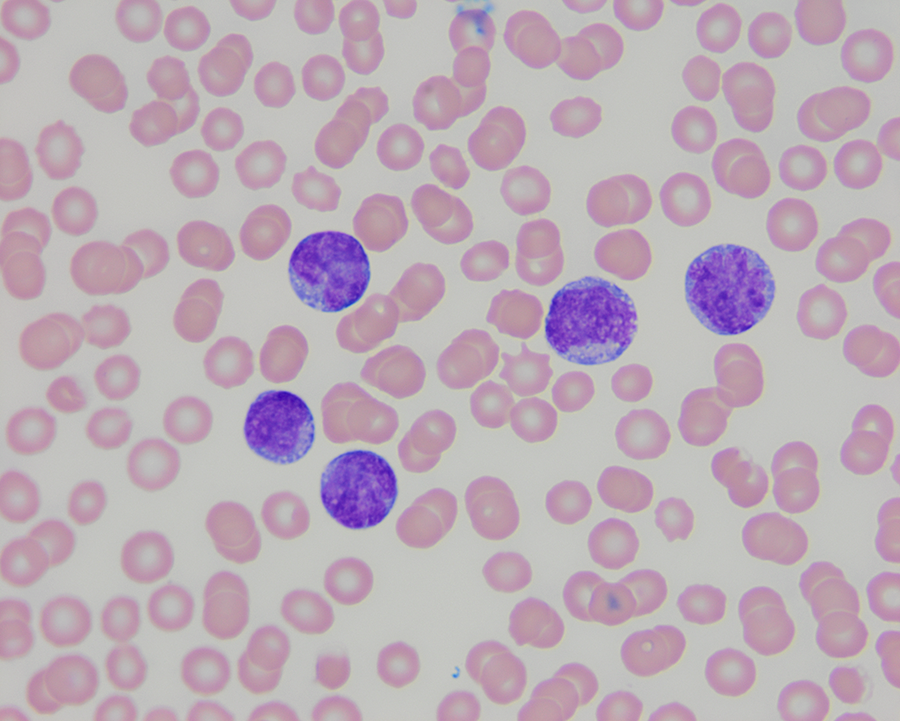

Currently, when dogs receive a diagnosis of AML, they have only a fraction of treatment options available to humans. Dr. Tracy Stokol, a professor in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences and veterinary clinical pathologist at the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine, wants to give dogs and their owners more information and better choices for fighting this aggressive disease. She received a grant from the Cornell Richard P. Riney Canine Health Center to investigate what the presence of different cancerous mutations reveals about how best to approach each dog's case.

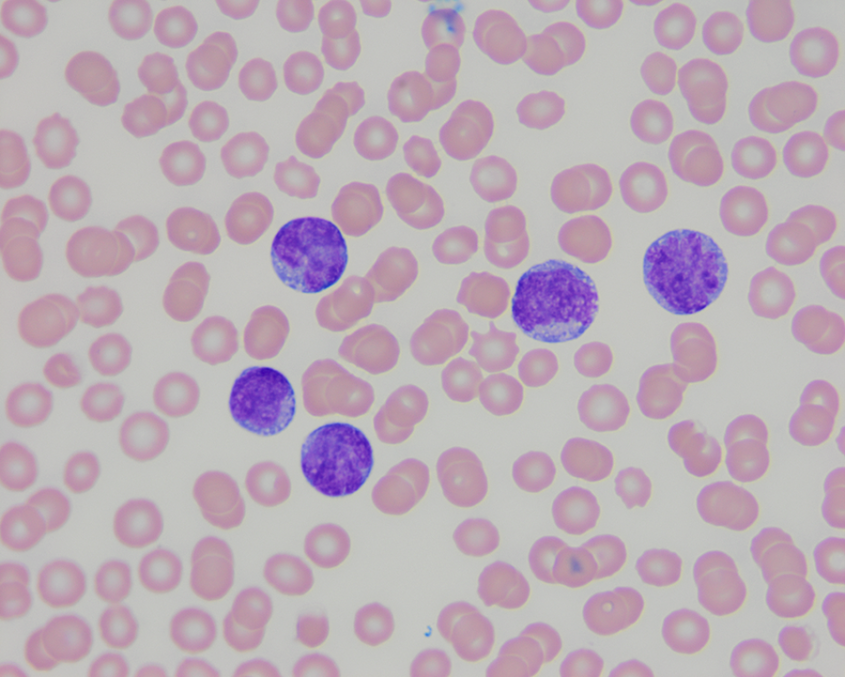

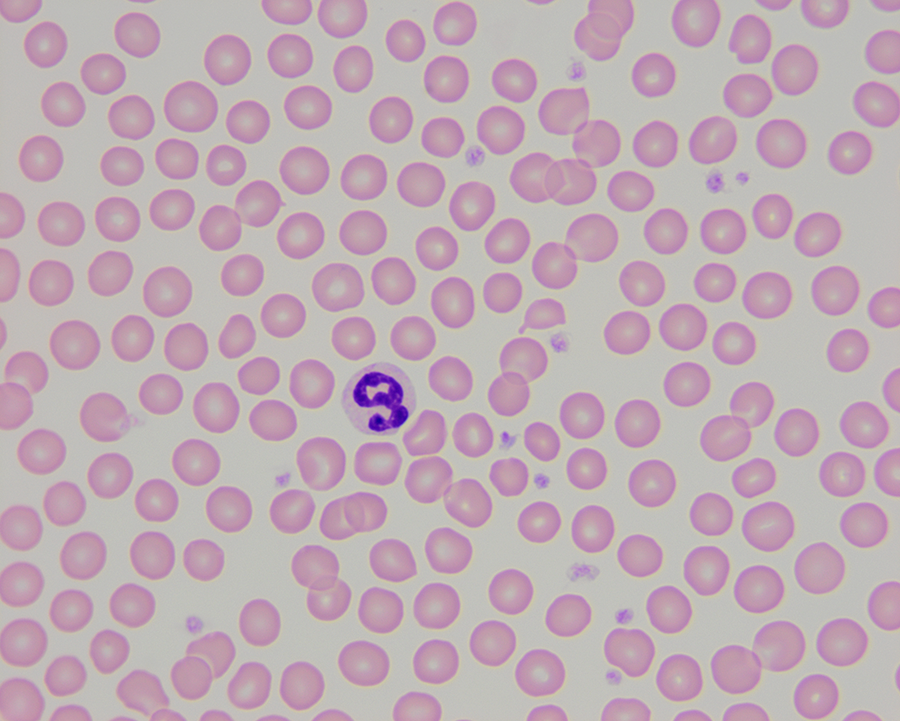

AML is a type of cancer that starts in the bone marrow and leads to the production of vast numbers of immature blood cells that ultimately crowd out the other normal cells in the blood. The cancer progresses quickly—healthy dogs suddenly become tired, stop eating, have enlarged lymph nodes or develop a fever. "It's devastating when you have this really happy dog, some of which are quite young, and then suddenly they develop an incurable disease, which is so rapidly fatal," Stokol said.

Stokol has long been fascinated by AML, starting with her training in veterinary clinical pathology, but the disease really hit home when a close family member died from AML. The death inspired her to pursue research on the canine disease more vigorously. "We're so far behind in veterinary medicine," said Stokol. "We're using drugs that are old in human medicine and it would be nice to be able to expand our treatment options."

The center funding will enable Stokol to analyze blood samples from 20 dogs diagnosed with AML along with collaborators at the University of Georgia, the University of Guelph and the University of Tennessee, veterinarians from specialty clinics, and a pathologist who specializes in human AML at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. They plan to compare DNA from the cancerous cells in the blood to DNA from a cheek swab to identify new mutations. Ultimately, they hope to link the mutations to different subtypes of AML, enabling genetic testing that could indicate whether newer drugs may be more effective than the standard treatment.

With the initial work funded by the Cornell Riney Canine Health Center, Stokol also recently received a grant from the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation that will extend the project for another two years and include 46 additional dogs.

Stokol is eager to recruit additional dogs. Veterinarians treating dogs suspected to have AML can contact her to be considered for the study, where they will receive complimentary diagnostic testing. The study may help future AML patients to live longer lives.

"I think we can do better than what we're doing now," Stokol said, "and at least give the owners more time with their dogs."

Written by Patricia Waldron