Freshwater Harmful Algal Blooms

For Animal Owners

What are freshwater harmful algal blooms (FHABs)?

- Cyanobacteria, sometimes called blue-green algae, are organisms that cause FHABs.

- Cyanobacteria are too small to see with the naked eye.

- Overgrowth forms FHABs that harm fish and other animals.

- Some FHABs are poisonous.

Can FHABs harm my animals?

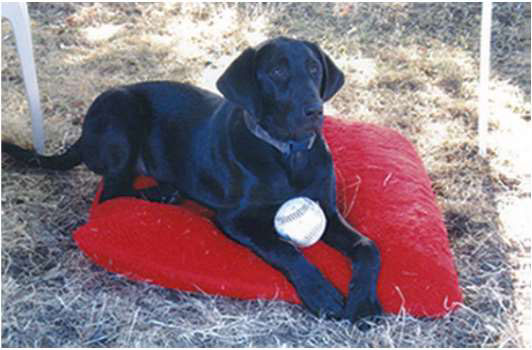

Poisonous FHABs can sicken or kill wild animals, farm animals, and pets, especially dogs.

- Dogs die from FHABs every year.

- The best protection is prevention!

- Avoid areas with visible HABs.

- View the New York Department of Environmental Contamination's HAB locator

How do FHABs happen?

3.4 billion year old stromatolite fossil. Stromatolites are colonies of cyanobacteria. Courtesy Wikipedia. Blooms can occur during warm weather and prefer still water.

- Cyanobacteria that cause FHABs have been around for 3.5 billion years.

- Cyanobacteria are small enough to be carried by wind and are found all over the world.

- Deadly FHABs are becoming more common, most likely due to pollution from agriculture and household products, and climate change causing warming.

What does FHAB poisoning in animals look like?

There are different kinds of FHABs, and they produce different signs:

- Skin contact can cause reddening and itching (cylindraspomopsin).

Drinking contaminated water can cause a variety of signs including:

- Seizures, tremors, and paralysis (anatoxins, saxitoxin).

- Time delay followed by vomiting, yellow skin, and bleeding (microcystin).

- Rapid progression to death in some cases.

What do FHABs look like?

- Because the organisms that cause FHABs are very small, you can’t see them with the naked eye, but when there are a large number present, you sometimes see a color change. All photos provided by Dr. Greg Boyer.

| Sometimes they float and look like patches of blue-green, green, or brown paint on the surface of the water. |

| |

| Sometimes they are found throughout the water and the water look like pea soup. |

| Sometimes they seem to form stripes in the water. |

| Sometimes they sink or die off and are no longer visible, but the water is still contaminated. No lake or pond is completely safe from HABs on warm days, but it’s best to avoid lakes and ponds if an HAB has been reported in the past 3 to 4 weeks. |

How do I keep my animals safe from FHABs?

- The only way to keep pets safe is to keep them away from FHABs. Here are some ways to prevent exposure:

- Keep farm animals safe by putting a fence around ponds or along lakes.

- Keep dogs safe by using a leash when walking near ponds or lakes.

- Keep dogs from swimming in or drinking from natural lakes and ponds where FHABs have been seen or during the warm weather conditions good for FHAB growth.

- If pets love playing in water or swimming, they will love a small swimming pool or lawn sprinkler.

Avoid FHABs by planning ahead before going boating, fishing, or swimming by checking for FHABs at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) Notifications Page.

What do I do if I see a FHAB?

- You can report FHABs to the New York State DEC Suspicious Algal Bloom Report Form at the link below: https://survey123.arcgis.com/share/66337b887ccd465ab6645c0a9c1bc5c0

- Include the specific location the suspected FHAB was seen.

- Include photographs of the suspected FHAB.

- You can also send location information and images and location to the New York State DEC Harmful Algal Blooms email address: ABsInfo@dec.ny.gov.

What do I do if my animal drinks contaminated water or gets it on its skin?

- Contact with a FHAB is a veterinary emergency.

- These are the steps to take if your animal physically contacts or drinks a possible FHAB:

- Immediately remove the animal from the source of the FHAB.

- For fur contact:

- Run clean tap or well water over the fur and skin using a hose or buckets.

- Run clean water over the animal for at least 5 minutes.

- Water should be clear as it runs off the skin and fur.

- Do not allow the animal to lick itself.

- Contact your veterinarian or an emergency veterinary clinic.

- Your animal needs to be seen by a veterinarian as soon as possible to assess and treat

- Poison Control Emergency hotlines:

- ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center: 888-426-4435 (may require consultation fee)

- Pet Poison Helpline: 855-764-7661 (may require consultation fee)

- New York Regional Poison Control Center: 800-222-1222 (for human exposures) for poisoning.

Helpful Links

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

- New York State Health Department Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

- New York State Confederation of Lakes Association (NYSFOLA) Harmful Algal Blooms

- US Centers for Disease Control One Health Harmful Algal Blooms

- ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center

- Pet Poison Helpline

For Veterinarians

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on history of exposure to a contaminated freshwater source. Appropriate clinical signs, as described below, further inform the diagnosis. Confirmation of the diagnosis is based on water source testing or diagnostic sample analysis.

Baseline blood testing should include a full serum chemistry.

Treatment depends on the cyanotoxin present, however, early intervention is critical.

- Early dermal decontamination: Flushing of contaminated skin is critical to prevent ingestion due to grooming. It also prevents toxin-related dermal irritation. Flushing should be continued for at least 5 minutes. Lavage water should be clear as it runs off the skin and coat.

- Gastrointestinal decontamination: Use emetics with caution. Cyanotoxins are rapid-acting and some are neurotoxic, increasing the potential for seizures. Sedation with gastric lavage can be considered for large ingestions.

- Activated charcoal has been administered within 2 hours of ingestion, but may not be effective against microcystin.

- Symptomatic and supportive.

Prognosis varies based on cyanotoxin, but in general, prognosis for symptomatic patients is poor to grave, but recovery from neurotoxins is complete.

Cyanotoxins

Major cyanotoxins of veterinary concern:

- Anatoxin-a

- Guanitoxin

- Saxitoxin

- Cylindrospermopsin

Microcystin

Microcystin is the most common cyanotoxin and is hepatotoxic. Nodularin is similar. Microcystin can be produced by Microcystis spp., Dolichospermum (Anabaena) spp.,

Planktothrix spp., and others. Nodularia spumigena produces nodularin.

Microcystin exposure can cause clinical signs in minutes to hours, sometimes leading to peracute shock. Expected clinical signs include diarrhea, vomiting, weakness, and coagulopathy. Survivors can later present with icterus, photosensitization, and immunosuppression.

Clinical chemistry abnormalities include increased ALT, ALP, CK, bilirubin, potassium, and potassium, increased coagulation times, and hypoalbuminemia.

Treatment includes supportive care and hepatoprotectants such as SAM-e and N-acetylcysteine. Activated charcoal has not been proven effective.

Prognosis is poor, but some animals recover with intensive management.

Anatoxin-a

Anatoxin-a is a neurotoxin that acts through stimulation of nicotinic receptors. Anatoxins are produced by Dolichospermum (Anabaena) spp., Planktothrix spp., Microcystis spp., Aphanizomenon spp., Phormidium spp., and Cyclindrospermum spp.

Because anatoxin-a is rapidly absorbed, clinical signs are almost immediate. Actions at the nicotinic receptor cause early muscle fasciculations, tremors, and generalized muscle rigidity which progresses to paralysis due to depolarizing neuromuscular blockade.

Treatment involves muscle relaxants, seizure control, and supportive care with emphasis on respiratory support. Benzodiazepines and barbiturates have been used for seizures control, but propofol may exacerbate respiratory compromise.

Prognosis is grave, but survivors recover completely.

Guanitoxin

Guanitoxin (formerly anatoxin-a(S)) is another neurotoxin with nicotinic and cholinergic effects due to inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Guanitoxin is produced by Dolichospermum (Anabaena) spp. Due to acetylcholinesterase inhibition, clinical signs include increased salivation and lacrimation, polyuria, diarrhea, vomiting, and nicotinic signs as described with guanitoxin. Central nervous system signs are not expected because guanitoxin does not cross the blood-brain barrier.

Treatment can include atropine to reverse life-threatening cholinergic signs, in addition to symptomatic and supportive care.

Prognosis is grave, but survivors recover completely.

Saxitoxin

Though most commonly associated with paralytic shellfish poisoning, saxitoxin is sometimes produced by Anabaena spp and blocks sodium ion channels. Saxitoxin poisoning has been reported in dogs, who presented with early vomiting, followed by paresis and paralysis, affecting the urinary bladder in one case. Progression to death occurred in as few as 2 hours. A transient elevation in liver enzymes was reported in one dog.

Treatment of affected dogs with supportive and symptomatic care was successful in some cases.

Prognosis, based on reported cases, was poor to fair and is likely dose dependent.

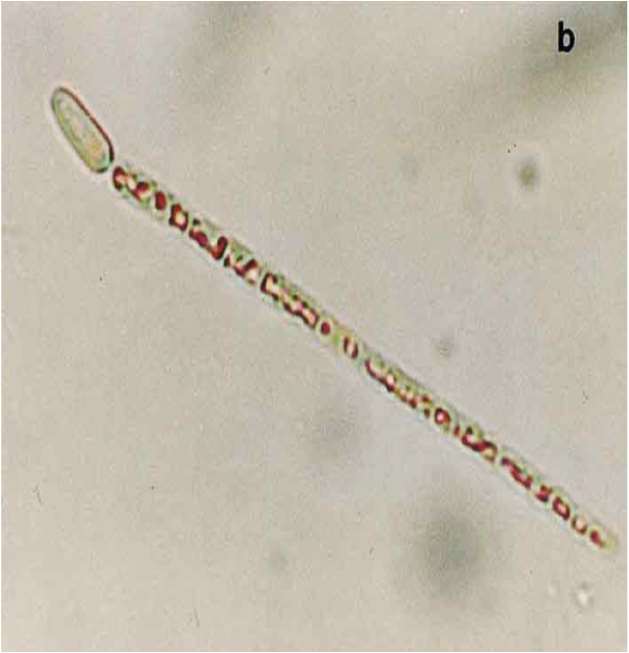

Cylindrospermopsin

76(9): 593.

Cylindrospermopsin is produced by Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and others. It acts by inhibiting protein synthesis and producing oxidative stress leading to irritation of the gastrointestinal tract and liver and kidney damage.

Clinical signs associated with cylindrospermopsin have been rarely reported in veterinary species, but are predominantly related to relatively chronic hepatotoxic effects, thus the recommended treatment is supportive care similar to microcystin exposure.

Further Reading

- Merck Veterinary Manual

- CDC Facts about Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms for Poison Center Professionals

- ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center

- Pet Poison Helpline