Clostridial Myositis

During the summer of 2023, the Animal Health Diagnostic Center (AHDC) diagnosed several cases of clostridial myositis (blackleg) in dairy heifers on farms throughout the northeastern U.S. One striking feature was the magnitude of the outbreaks; some farms lost multiple animals within a few days, and on two farms, large numbers of animals died.

The most notable outbreak resulted in 25 dead heifers, all 7-9 months old. These animals presented with weakness before rapidly becoming recumbent, cold, tachypneic, and dying or being euthanized within 24 hours. The first necropsies on euthanized heifers did not reveal any gross abnormalities. Aqueous humor was tested to rule out nitrate/nitrite toxicosis. Fecal flotations were performed to rule out Strongyloides papillosus as a cause of sudden death. In the middle of this 11-day outbreak, it was noted that most affected animals had some degree of swelling in one or more limbs.

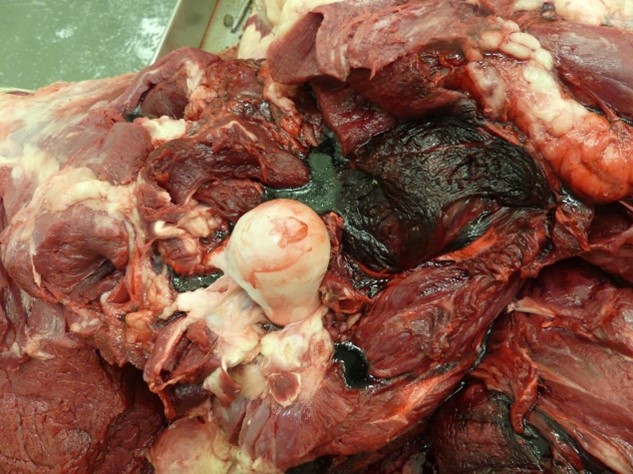

Additional necropsies performed on animals who died (not euthanized) on this farm revealed gross findings characteristic of clostridial myositis with severe, multifocal, generalized, acute emphysema, hemorrhage, and edema of the skeletal muscle and myofascial planes (Figure 1). The diagnosis was confirmed with growth of Clostridium chauvoei on anaerobic culture and a positive C. chauvoei fluorescent antibody stain, both performed on affected skeletal muscle tissue.

No recent injections had been administered and no common sources of bruising were evident in the three pens that housed affected animals, but a recent feed purchase had occurred. The farm had not previously included a clostridial vaccine in their protocol and initiated vaccination of heifers with a multivalent clostridial organism/toxoid product amid this outbreak. Although immunity takes weeks to develop, vaccination is highly effective at preventing blackleg following natural exposure.

Clostridial myositis occurs most commonly in cattle between 6 months and 2 years of age, typically in summer and fall during periods of high rainfall.1 The spores of C. chauvoei survive in soil for many years and can be ingested by cattle in contaminated feed. The classic pathogenesis model states that ingested spores are absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed to various tissues, including skeletal and cardiac muscle. They can remain dormant for long periods until trauma and necrosis of the muscle creates the ideal anaerobic environment for the spores to germinate.3 This model, however, does not account for large outbreaks like the one described above. In these situations, it is thought that ingestion of a heavily contaminated feedstuff may lead to translocation across the gut barrier into the bloodstream, resulting in bacteremia or sporemia directly from the intestine.3 The predilection for muscle colonization in these outbreaks is not clear. In clostridial myositis cases involving only cardiac tissue, it is important to consider selenium deficiency with secondary myocardial necrosis as a possible underlying etiology.2

Figure 1

References:

- Abreu CC, Edwards EE, Edwards JF, et al. Blackleg in cattle: A case report of fetal infection and a literature review. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2017;29(5):612-621. doi:10.1177/1040638717713796

- Glastonbury JR, et al. Clostridial myocarditis in lambs. Aust Vet J 1988; 65:208–209.

- Uzal, Francisco A., et al., eds. Clostridial Diseases of Animals. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.