Annual Report 2022

The Future of Animal Health

The future is looking bright for the Baker Institute for Animal Health. For a research institute rooted in such a strong history of animal health discoveries, one thing that continues to evolve is the landscape of interdisciplinary research among the growing labs and faculty. Reflecting back on 2022, the Institute took many important steps to continue that trajectory forward, and the future looks bright indeed.

2022 resulted in the successful recruitment of some of the best rising stars in our industry to join the Baker Institute. This follows the addition of Laura Goodman, Ph.D., Department of Public and Ecosystem Health, who joined the Baker Faculty officially in 2021.

Joining the team of experts at Baker in 2022 are Jacquelyn Evans, Ph.D., and Sarah Caddy, MA, VetMB, Ph.D., DACVM, FRCVS, and in the spring of 2023, Mandi de Mestre, BVSc (Hons) Ph.D., MRCVS, PGCAP, FHEA, joined the Baker community as well.

Bringing with them fresh perspectives, unique experiences, and vast world-wide connections - with some of their experience tied to the foundational learning that two of them actually experienced as trainees here at Baker in years past - these researchers are laying the groundwork for the future health of our companion animals.

An Introduction to our Two Newest Faculty

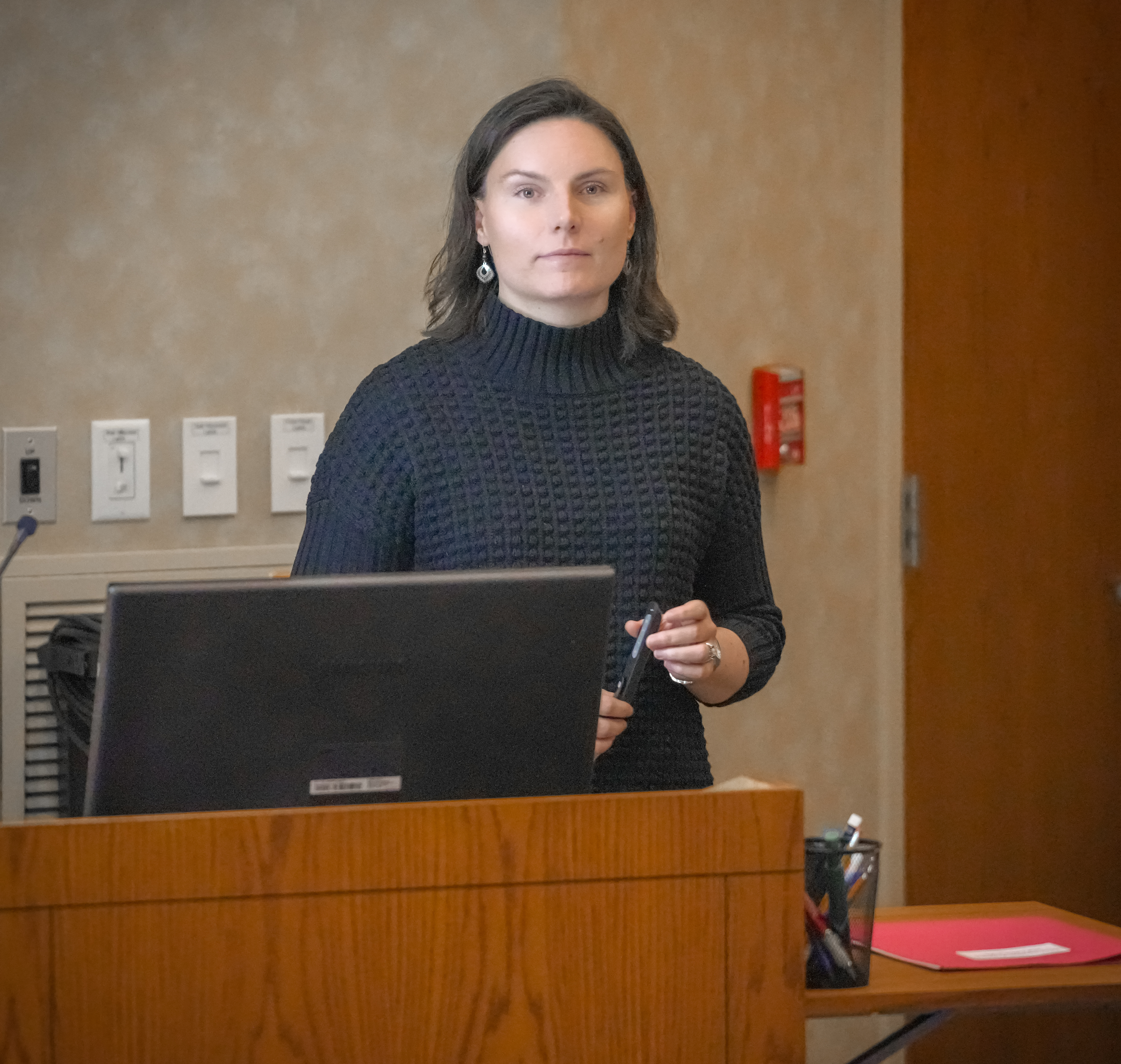

Dr. Jacquelyn Evans joined the Baker Institute and the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Biomedical Sciences as an assistant professor last year.

A native of Michigan (who mostly grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina), she specializes in hereditary diseases in dogs – a focus that developed serendipitously when she entered Clemson University in South Carolina as an undergraduate. “I was interested in genetics thanks to an AP Biology class I’d taken in high school, but at the time, there wasn’t anyone in the genetics and biochemistry department working on human genetics,” Evans recalled. “So I joined Dr. Leigh Anne Clark’s canine genetics lab through the undergraduate research program. That’s how I ended up in veterinary-based research and really loved it.”

In fact, she stayed on to complete her Ph.D. in Clark’s lab, working to identify variants in three different genes that interact in multiple combinations to increase the risk for dermatomyositis, an autoimmune disease in collies and Shetland sheepdogs. “That particular project really piqued my interest in more complex diseases that are controlled by more than just a single gene,” Evans said.

By the time Evans decided to come to Cornell, she was consciously choosing to conduct her research at a veterinary school, where she can marry her genetic expertise with the clinical skill sets of her colleagues and apply them to real-life patients. “I’ve started a few projects with clinicians at the hospital, which is very exciting,” she said. Evans felt especially drawn to the Baker Institute.

“Baker has such a great history of animal health research and the specific emphasis on veterinary research is unique,” she explained.

She is the first faculty member at the college to be supported by the new Cornell Richard P. Riney Canine Health Center, which is dedicated to research, outreach, and engagement that helps dogs live longer, healthier, and happier lives. Endowed with a $30 million gift from the Riney Family Foundation, the center brings together the work of some 50 researchers studying canine health-related topics across many departments and builds on existing strengths in research on cancer, genetics and genomics, infectious diseases, and immunology.

Evans, for one, appreciates the support she has received through the Canine Health Center’s internal grants program, which recently funded her study on chronic superficial keratitis in German shepherd dogs. Also known as pannus, the progressive disease causes lesions to form across the eye and requires aggressive treatment with eye drops, which can become a financial burden for some pet owners. “It doesn’t have a direct disease counterpart in people, but it is a significant issue for German shepherd dogs, which is a breed working in many roles – as guide dogs or in the police and military force – where they really need their sight,” Evans said. The prevalence of pannus in a specific breed is a clue to its genetic origins. (Evans is currently recruiting dogs to participate in her study and welcomes inquiries.)

Evans’s second major focus is on gastric cancer – an interest that grew out of research she conducted as a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health with Dr. Elaine Ostrander, a leader in the field of dog genetics, specifically canine cancer and other complex diseases. Their work examined genetic factors contributing to the risk for histiocytic sarcoma, a lethal cancer common in flat-coated retrievers and Bernese mountain dogs. Now Evans has turned her attention to gastric adenocarcinoma, a relatively rare cancer that occurs more frequently in certain breeds, such as the Belgian sheepdog (Groenendael) and Belgian Tervuren, and often remains undiagnosed until it has reached an advanced stage.

“The ultimate goal in my work is to develop genetic test that can be used in breeding decisions to produce healthier dogs,” Evans said. “And understanding more about the genes that cause the disease can lead to new treatments and therapy options as well.” Tests developed from her graduate work on dermatomyositis, for example, allow breeders to look at the genetic variants in a dog and assess the animal’s individual risk of developing the autoimmune disease in its lifetime. Through informed decisions breeders may reduce the occurrence of the disease over time. A veterinary dermatologist also used her lab’s tests to assist in diagnosis of dogs in a clinical trial to create new therapies. “Developing this risk assessment and having it lead directly to a translational study is probably the project I’ve been most proud of,” Evans said.

While her work centers on dogs, she hopes its impacts will continue to draw wider circles. “One issue with trying to do genetic studies of people, especially for rare diseases, is that sometimes you can’t collect enough samples to get really informative results,” Evans explained. “In dogs, where we have these higher incidences within breeds, and just based on their breeding structure, we don’t need as many samples. A lot of times we can find mutations more easily in the dog model than we can in people. So hopefully what we learn from these projects will tell us more about what’s going on in diseases that affect multiple species.”

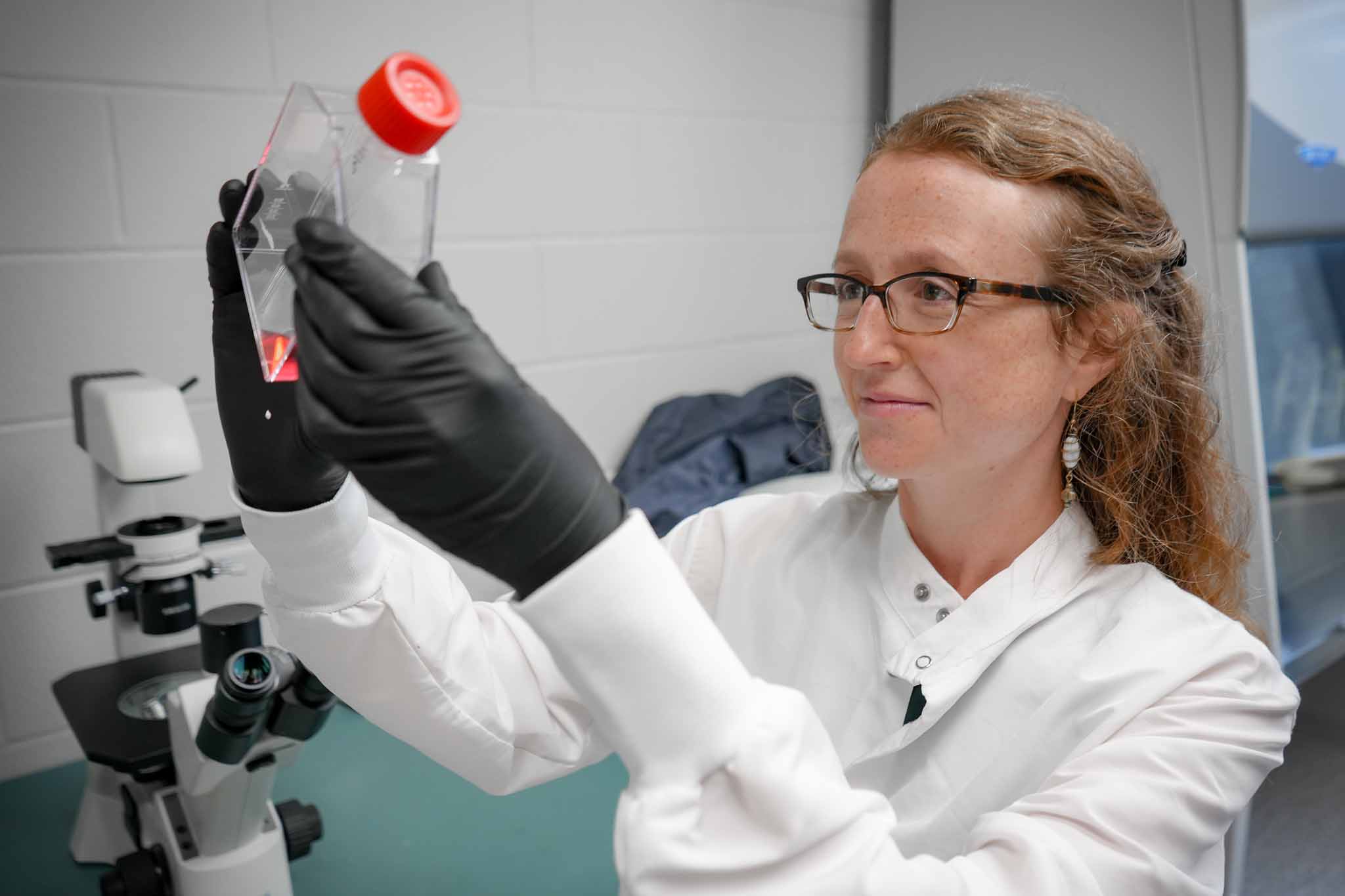

Dr. Sarah Caddy’s love for animals began early. She greatly enjoyed visiting her grandfather’s sheep farm in North Yorkshire, England as a child. But it wasn’t until the native of Haywards Heath, a small town in the south of England, joined the Young Farmers Club at her school that she realized animals were her vocation. “The school had a farm, which was very unusual, and cattle showing, milking cows, looking after pigs really changed what I wanted to do with my life and put me on a path to being a vet,” said Caddy, who joined the CVM faculty as an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology last year.

The specialist in virology and antibodies has come full circle to the Baker Institute, where she first felt the spark for veterinary research in 2007. A fourth-year student at the Cambridge Veterinary School at the time, Caddy spent the summer in Ithaca as part of the Leadership Program for Veterinary Students. Associate professor of virology John Parker, Ph.D. ’99 introduced her not only to his academic work but also to Dr. Ian Goodfellow, who would become her Ph.D. mentor at Imperial College London a few years later. “Until I started vet school, I didn’t know any scientists or academics,” Caddy recalled. “But once I got to do a short research project, I was hooked. And John Parker had a massive influence on those early stages. It’s fantastic to be the lab directly below his at the Baker Institute.”

Caddy’s doctoral work in virology focused on identifying one of the host factors – a carbohydrate receptor – for binding canine norovirus. “This was a relatively unknown virus, and it was exciting to be at the forefront of research into this virus at the time,” she said, crediting Goodfellow with giving her the scientific freedom and encouragement she needed to complete her degree. Caddy is also proud to have solved a long-standing puzzle by finally proving a link between intracellular antibodies and T-cell activation, a challenging project she tackled as a postdoctoral fellow at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. Boosted by this experience, she successfully applied for her own independent research funding from the Wellcome Trust, a charitable foundation focused on health research, which she took to the Department of Medicine at the University of Cambridge as a clinical research fellow.

When it came time to consider the next steps in her career, the Baker Institute was an obvious choice. “It just seemed perfect, like everything was coming together,” Caddy said.

“The veterinary leadership program had really shown me the potential of researching in a world class venue and played a huge part in my decision to come to the U.S.” The breadth and depth of virology and immunology research taking place at Cornell was another factor, as was the opportunity to work with multiple species. “I opted to get most of my research training in medical schools, but to now finally come back to a vet school has been absolutely fantastic,” Caddy explained. Even Ithaca, she says, has lived up to its reputation as a small town with a great quality of life, where she is happy to rebuild the garden and houseplant collection she had to leave behind in England.

In growing her lab, Caddy is focusing on two main projects. For one, she is looking at the relationship between antibodies and T cells. Her recent work has found that some antibodies can enhance antigen presentation via a unique intracellular antibody receptor called TRIM21. The Caddy lab now aims to uncover the molecular details and wider significance of this unusual pathway. “This is a really new avenue of research,” Caddy said. “We hope we can harness this knowledge to potentially develop new vaccine approaches.” She is also studying the transfer of antibodies from mothers to infants in mammalian species. Maternal antibodies can block infant immune responses so that vaccines are sometimes less effective in young children and animals. “Since we don't know exactly how this happens yet, we cannot come up with clever solutions to get around this problem - yet,” Caddy said.

While Caddy’s team is conducting most of these studies with mice, she has interest in bovines, and she is looking forward to developing some canine-specific projects. (She is also actively looking to recruit more enthusiastic researchers with an interest in virus and antibodies and invites applications to her vibrant international research lab.) Whatever the species, Caddy – recently awarded a Fellowship by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons for her “meritorious contributions to knowledge” – hopes her research will lead to improved preventive measures for humans and animals. “It’s my career goal to be instrumental in developing a new vaccine,” she said. “I would love that.”

Continuing Towards the Future

“One of my biggest joys here at the Baker Institute is having the opportunity to take part in the teaching of the next generation of veterinary researchers in our industry. The trainees that have been a part of the Van de Walle lab, or working and studying among the other labs here, have become part of the history of the Institute and have contributed in immeasurable ways to the discoveries and advancements made while they were here,” states Gerlinde Van de Walle, D.V.M, Ph.D., Interim Director of the Baker Institute for Animal Health and faculty researcher at the Institute.

“Just one example from this past year is of former trainee, and our most recent graduate from the Van de Walle research team, Mason Jager, D.V.M ‘12, Ph.D. ‘22, DACVP. Mason is an anatomic pathologist who came to our lab in 2019 to pursue his graduate studies on the replication kinetics of a novel parvovirus that causes hepatitis in horses. Research on parvovirus in dogs is deeply embedded in the successful history of the Institute and seeing parvovirus research being expanded to other companion animals illustrates the Institute’s forward trajectory into the future” Van de Walle says.

Jager graduated in the spring of 2022 and continues his research in his newly established lab here at Cornell in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences as a pre-tenure track assistant research professor”.

Training is a focal part of the mission at the Institute, and the environment here lends itself as a truly unique experience for trainees, with the cross-disciplinary lab spaces, shared equipment and resources at the ready for labs, and the community-minded atmosphere. When people walk through our halls and see portrait after portrait of trainees as you pass by, the breadth of research and expertise is palpable. “It’s so wonderful to see people like Laura, Sarah and others return as faculty, collaborators, and/or seminar speakers years later,” continues Van de Walle.

The attraction must be strong, as the return of trainees to join Baker as faculty has also been the path for others who are part of the long-standing list of experts at the Institute including John S. L. Parker, BVMS, Ph.D. ‘99, and Colin R. Parrish, Ph. .D. ’84.

We welcome the joining of forces and look forward to what the future holds.

Written by Olivia Hall.