Research

Catching the Silent Killer: Toward a Better Diagnosis for Canine Hemangiosarcoma

Many dog owners first hear about hemangiosarcoma at an emergency visit to the vet. Their dog, which previously appeared healthy, is now bleeding internally from a mass on the spleen. At that critical time, veterinarians cannot easily tell whether the mass is potentially deadly, and currently the only course of action is sending a sample away to a pathologist for testing to be able to distinguish between a fatal hemangiosarcoma or a benign growth. Thus, owners face a terrible choice: either euthanize their beloved companion because the growth is likely to be hemangiosarcoma or pay for an expensive surgery in the hope that it's not.

Hemangiosarcoma is called "the silent killer" because it often shows no signs until it has already become untreatable. To help catch this disease before it becomes fatal, Dr. Scott Coonrod, PhD, the Judy Wilpon Professor of Cancer Biology and Director of the Baker Institute for Animal Health at the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine, is leading an investigation into the basic biology of the tumor. The study uses next-generation sequencing technology to find differences among hemangiosarcoma, benign tumors and healthy spleen tissue. The results could lead to diagnostic tests for screening at-risk dogs and rapidly identifying cancer in the clinic.

"When veterinarians in the ER are imaging these masses on the spleen, they can’t tell whether these growths are hemangiosarcoma or just hyperplasia, which is much more benign," said Coonrod. "There needs to be some way to make a faster determination about whether the growth is benign or malignant so the owners can make informed, on-the-spot, decisions about next steps."

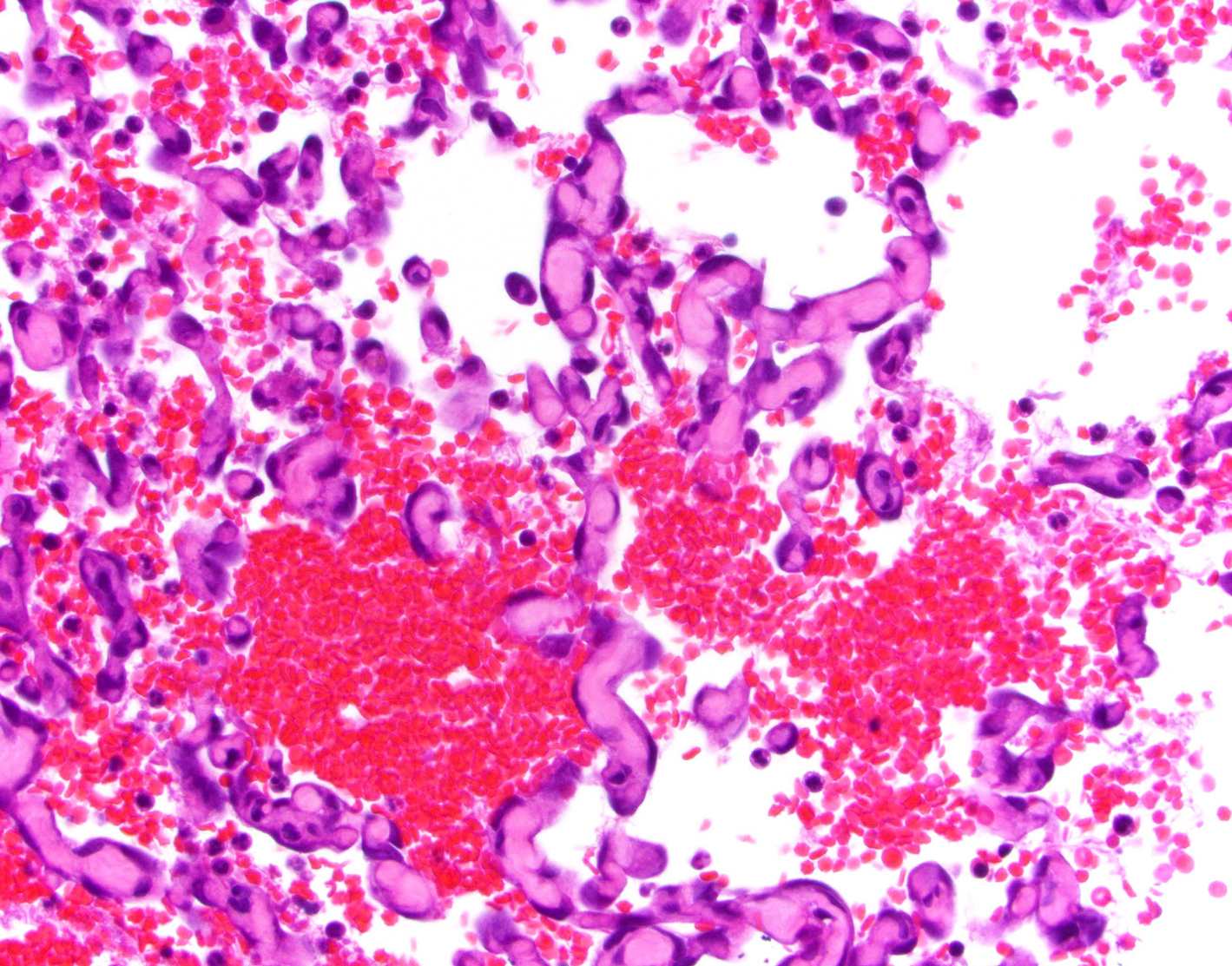

Hemangiosarcoma is an aggressive cancer that grows from the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. About two-thirds of cases occur in the spleen, but it can also arise in the liver, heart, skin and other less common locations. Standard treatment for the splenic form involves removing the spleen and chemotherapy. However, treatment usually only prolongs the dog's life by a few months.

"Hemangiosarcoma is universally fatal," said Dr. Andrew Miller, DVM '05, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences in the section of anatomic pathology at the College of Veterinary Medicine and a collaborator on the project. "We don't have good treatments and we don't understand the pathogenesis."

Dogs Helping Dogs Through the Biobank

Coonrod's team has been conducting research on hemangiosarcoma and investigating differences between healthy spleen tissue since 2016. Research like this is made possible through a variety of funding streams, including support from the College Research Council that oversees internal grant opportunities, as well as gifts from Baker Institute’s generous supporters. Some of the groups and individuals who have had a special interest in this cancer research include long-time friend of the Baker Institute and Advisory Council member, Judy Wilpon, who made the first significant gift to support Coonrod’s HSA research. Since then, additional supporters have contributed to this important research including donor Jake Holshuh, ClancysCure for Cancer, and organizers of the non-profit Kyle’s Legacy, of which the Baker Institute is thankful to all.

Dr. Chinatsu Mukai, PhD, formerly a research associate at the Baker Institute and now a scientist at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research in Maryland, has been a key researcher on the project. "Her experimental skills, knowledge of canine physiology and genomics expertise have allowed the project to fully develop to the point where it is now poised to make important new discoveries," Coonrod said. "The research is truly a collaborative effort across college units as well."

The Cornell Veterinary Biobank has collected hemangiosarcoma samples for Coonrod from patients seen at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals since 2016. "We have a phenomenal team, led by Susan Garrison, LVT, that coordinates the tissue collection at surgery," said Dr. Marta Castelhano, DVM, MVSc, director of the Biobank. "The animals often don't have long to live, so it's quite a partnership with the owners to ask them to improve the lives of other dogs when they’re losing their own," said Castelhano.

With the owners' consent, a board-certified pathologist takes two "mirror image" tumor samples from the spleen, with half going to Coonrod’s research and half to the Biobank. Miller advises on the sample collection with the biobank specialists just outside the operating room and a pathologist examines the tissue under the microscope to make a diagnosis.

"Within minutes of the tumor being removed from the dog, it's in the hands of the researchers and Biobank specialists," Castelhano said. "We deliver the fresh samples to Dr. Coonrod’s team immediately after collection, and flash freeze and store the biobank aliquots for future research."

Mukai analyzed these samples using an advanced sequencing technology called ChRO-seq, developed by Dr. Charles Danko, PhD, the Robert N. Noyce Associate Professor in Life Science and Technology at the Baker Institute. ChRO-seq detects the location of tiny molecular switches called transcription factors that bind to the genome to turn genes on and off. The technology creates a map of the switches, revealing which genes are active in the tissues.

Better Biomarkers

The researchers compared the genes turned on in healthy spleen tissue and hemangiosarcoma tumors and discovered one prominent difference. The cancerous tissues develop an especially thick extracellular matrix, the 3D lattice of collagen and other molecules that support the surrounding cells. Hemangiosarcoma is packed with networks of blood vessels — that's why they bleed so much when they rupture — and the denser matrix likely acts as a scaffold supporting those vessels.

Credit: Pixabay

In a paper published in 2020, the team reports that hemangiosarcoma tissue overproduces two biomolecules that make up the extracellular matrix. These molecules have the potential to serve as biomarkers that indicate the presence of the cancer.

"With our research, we are hoping to develop a panel of biomarkers that can be used to detect early onset of hemangiosarcoma," Mukai said. "Also, we are working to identify the biomolecules from serum so that dogs can be diagnosed by a non-invasive test rather than from a needle biopsy, which carries a risk of rupturing the spleen."

With a new grant from the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation, Inc. (CHF), Coonrod's group is using ChRO-seq to look for biomarkers that differentiate hemangiosarcoma from the benign tumor hyperplasia.

"CHF and its donors are committed to fighting hemangiosarcoma through novel approaches," said Andrea Fiumefreddo, Vice President of Programs and Operations for the CHF. "Dr. Coonrod’s study has the potential to add to existing and limited treatment options and improve survival for dogs with this devastating disease — a vital win for our canine companions and the families that love them.”

Ideally, these biomarkers could be developed into a rapid diagnostic test for use in the clinic to differentiate between benign and malignant tumors when a dog arrives with a mass on its spleen. Dogs with hyperplasia can have many more years of life after the spleen is removed. "Those dogs do great, and they don't even care that they don't have a spleen," Miller said.

The researchers have analyzed about 40 tissue samples, with plans to add even more. They are beginning to identify several subtypes of hemangiosarcoma tumors with distinct profiles of active genes. By knowing which genes and pathways are active in these tumors, the researchers hope to be able to identify known cancer pathways that can be targeted by existing drugs. "This personalizes the tumor so veterinarians can make more informed decisions about the dog's prognosis and what types of therapies might be more suitable," Coonrod said.

While this work is just the first step toward commercial diagnostic tests and better cancer treatments, it is vital to transforming our understanding of this fatal disease. Coonrod hopes this research may one day give owners better options at the clinic when facing down a possible diagnosis of hemangiosarcoma.

Meet our researchers - Learn about our research:

Anthrax arms race helped Europeans evolve against deadly disease

Genetic study of Arabian horses challenges some common beliefs about the ancient breed

Researchers explore promising treatment for MRSA ‘superbug’

Companion Animals and Zoonotic Risk

New test offers clarity for couples struggling to conceive

Reovirus σ3 protein limits interferon expression and cell death induction