Training

Beyond Baker: Training the Next Generation of Scientists

The Baker Institute has been home to more than 300 graduate students, postdocs, research associates and visiting scientists in its more than 70-year history. Baker has welcomed researchers from around the world — at career stages from high school students to professors — with diverse interests across the field of animal health. These collaborations have yielded pioneering and interdisciplinary discoveries and cultivated the minds of young scientists; with the trainees going on to tackle some of the most challenging issues in veterinary medicine and biomedical research, filling vital positions in academia, industry and government labs.

Baker is a fertile training ground for early-career researchers because the faculty care, not only focusing on producing high quality research, but also on training high quality researchers. "The dual mission of the Baker Institute is to better the lives of companion animals through research and to train the next generation of scientist. Therefore, with this mission, our faculty really put in the extra effort into working with our trainees," said Dr. Scott Coonrod, PhD, the Judy Wilpon Professor of Cancer Biology and Director of the Baker Institute. "We want to ensure that everybody who comes through the Baker Institute gets world-class training so they can succeed in their future endeavors. We try to create the right environment for trainees to really optimize their time here, so when they're finished, they continue to do great things."

From Basic Cancer Biology to Finding New Cures: Chinatsu Mukai

Dr. Chinatsu Mukai, PhD, developed an interest in cancer research during her time at the Baker Institute and recently joined the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research in Maryland. Mukai was a co-investigator and research associate in Coonrod's lab using next-generation sequencing technology to investigate the biology of canine hemangiosarcoma. "She really drove this project," said Coonrod. "Now she's going to be even more heavily involved in cancer research. It's a very good move for her."

Mukai's position in the Coonrod lab wasn't her first time at the institute. Initially she joined the lab of Dr. Alexander Travis, VMD, PhD, as a postdoctoral associate after finishing her PhD at the University of Tokyo, in Japan in 2005. After completing her postdoc, Mukai returned to the University of Tokyo as an assistant professor, a position that primarily involved teaching.

Realizing that she missed research, Mukai returned to the Travis lab as a research associate in 2011. She studied enzymes in sperm that break down glucose to yield energy, and how these enzymes could be harnessed to power tiny implantable medical devices. Mukai also worked on Travis' canine In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) project, applying a gene editing technique called CRISPR in dogs. She had her own baby during this project, and was excited for her son, Kento, to meet Bonnie, an adopted IVF dog from the lab, at the annual Baker picnic.

Through her diverse experiences at the Baker Institute, Mukai has amassed a wealth of expertise in areas ranging from protein engineering and reproductive biology to gene editing and bioinformatics. "Every experience helped me grow to the scientist I am now," Mukai said. "I have a very deep understanding of many different fields."

At the Frederick National Laboratory, Mukai is applying those experiences in the Biopharmaceutical Development Program. The program advances novel pharmaceuticals for clinical trials to support the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and other government agencies. "I am very excited about this transition," Mukai said, "and happy to work for human medicine."

An Emerging Leader in Equine Liver Disease: Joy Tomlinson

In just five years at the Baker Institute, Dr. Joy Tomlinson, DVM, PhD, has established herself as a leading researcher in the field of equine liver disease.

After completing her veterinary degree and a clinical research fellowship at Cornell, Tomlinson joined the lab of Dr. Gerlinde Van de Walle, DVM, PhD, in 2016 for her PhD research. She did extensive work to show that the cause of Theiler's disease, a mysterious viral hepatitis that often arises after horses receive antitoxins or other blood products and is the leading cause of liver failure in horses, is caused by an equine parvovirus. She demonstrated that apart from accidental transmission through blood products, it also likely passes between horses through fluids from the nose and mouth. Now, she is investigating how the virus spreads through a herd during an outbreak and why certain horses suffer few symptoms from the virus while others progress to liver failure.

Tomlinson is also working on an equine liver virus called equine hepacivirus that is similar to hepatitis C and may be useful as a model of human disease. She suspects that the virus is responsible for large numbers of cases of severe liver disease. "I'm hoping that between these two viruses, we'll be able to explain a lot more of the liver disease in horses than we have before," said Tomlinson, "and that potentially we will be able to develop vaccines or treatments for one or both viruses."

The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) has given Tomlinson the AAEP 2021 Research Award in recognition of this work. Previously, Tomlinson was a co-vice president of the student chapter of AAEP during her final year in vet school, and she recently contributed to AAEP's official Equine Parvovirus-Hepatitis Virus Guidelines.

"The work that Dr. Tomlinson has done at Cornell University in the field of equine hepatitis viruses has revolutionized the way we diagnose, treat and prevent equine liver disease, and has given us an important understanding of Theiler’s disease, a costly disorder that has mystified veterinarians for over a century," said Dr. Raymond Sweeney, VMD of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Sweeney nominated her for the award with Dr. Thomas Divers, DVM of Cornell and Dr. Doug Antczak, VMD, PhD of the Baker Institute.

"Dr. Tomlinson has at an early age established herself as a leading researcher in equine medicine," said Divers. "Her research on equine viral hepatitis has been of both high scientific quality and practical application, and she is widely recognized as a world leader in this area."

In yet another honor, Phi Zeta, the national honor society of veterinary medicine, awarded Tomlinson the Best Basic Science Paper from a Veterinarian for her paper, "Tropism, pathology, and transmission of equine parvovirus-hepatitis," and Tomlinson recently, she received a major grant with Dr. Van de Walle to support her equine parvovirus work going forward.

"Gerlinde has been great at pushing me to be independent and allowing me to take those steps," said Tomlinson. "We've had strong collaboration with other people here at the institute that has really enhanced our efforts. Baker is a wonderful place to work."

Laying the Foundation for a Career in Arthritis Research: Lisa Fortier

Experiences at Baker can have a long-lasting impact on a trainee's career. Dr. Lisa Fortier, DVM, PhD ‘98, former James Law Professor of Surgery at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, learned how to think, write and lead like a scientist at Baker. These are lessons that will serve her well as the newly named Editor-in-Chief and Division Director of Publications at the American Veterinarian Medical Association (AVMA).

After earning her DVM from Colorado State University in 1991, Fortier said it was an obvious choice to join the Baker Institute for her graduate work in the lab of Dr. George Lust, a world-renowned expert in hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis in dogs.

"Every week, George and I sat down and just had a conversation about cartilage," Fortier said. Dr. Nancy Burton-Wurster, a fellow hip dysplasia expert, shared an office with Lust and frequently joined in the conversations. "I was very, very fortunate," said Fortier. "A lot of the work they were doing in hip dysplasia provided the foundation for my laboratory and clinical career."

Fortier's work focuses on the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying arthritis in horses. "The research can make an immediate clinical difference to human and animal patients – horses and dogs alike."

She has received more than $20 million in research funding from the National Institutes of Health and other sources for this work, and credits Lust with teaching her to carefully craft her writing. "He is a huge reason why I've been successful in writing grant proposals and getting manuscripts accepted, and it's also how I train my own graduate students," Fortier said.

Fortier is in phased retirement at Cornell, allowing for time to complete on-going projects and see her PhD students complete their thesis programs. At the AVMA, Fortier will use the skills she first honed at Baker to share new research with veterinarians nationwide. “Throughout her career, Dr. Fortier has distinguished herself as a clinician, scientist, educator and communicator,” said Dr. Douglas Kratt, immediate past AVMA President. “We are delighted that she will be bringing her expertise as a surgeon, as the author of more than 250 publications, and as an editor to her new position leading AVMA’s veterinary journals.”

Chasing Pandemics: Dina Tresnan

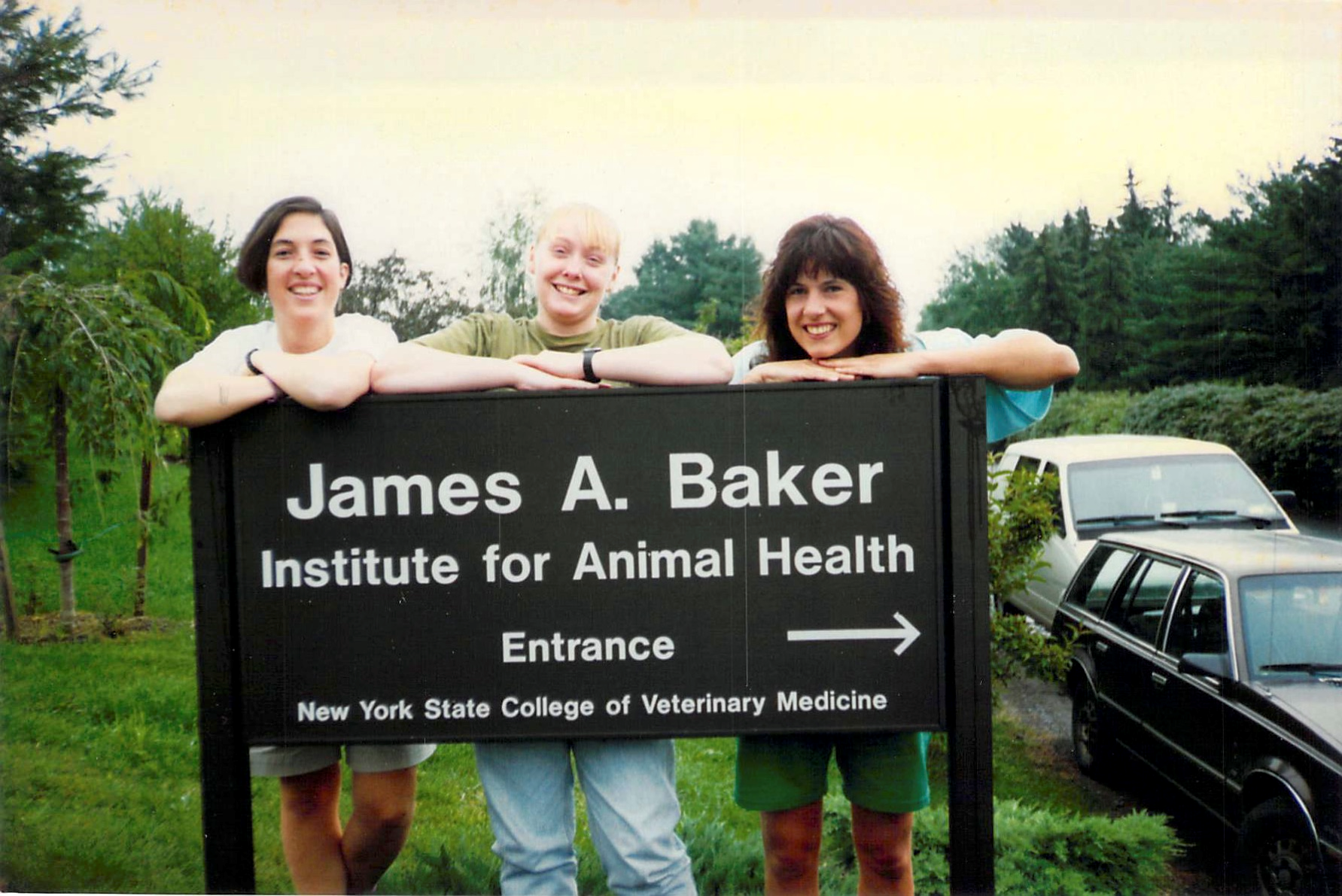

When Dr. Dina Tresnan, DVM, PhD, came to the Baker Institute in 1991, she could never have imagined that the experience would set her on a path to working on a vaccine for the most devastating pandemic since the 1918 flu.

Tresnan is the Disease Area Cluster Lead for Immuno-Oncology in Worldwide Safety at Pfizer Inc., where she leads safety surveillance and risk management for new and established immuno-oncology therapies. "We monitor and assess the safety profile of medicines, including vaccines, to ensure that the benefit outweighs the risk," said Tresnan. For the past two years, she has been instrumental in evaluating the safety of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, the first to receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Tresnan is fascinated by the interactions that occur between a virus and its host, and the molecular details that allow a virus to jump from one animal to another — or to humans. That fascination led her to the lab of Dr. Colin Parrish, PhD, the John M. Olin Professor of Virology, where she studied a previous global pandemic in dogs: canine parvovirus, which evolved from a cat virus. For her PhD, she characterized the host cell receptor that allows canine parvovirus to enter the canine cell and initiate replication.

"My experiences at Baker gave me a really strong foundation for scientific experimentation in virology and immunology," said Tresnan. "As we develop drugs with newer technologies, having a scientific and molecular background is a real strength."

Tresnan had previously completed her veterinary degree at the University of California, Davis, and successfully applied for a five-year physician-scientist award from the National Institutes of Health while at Baker. It funded the end of her PhD research and her first few years as an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. There, she partnered with Dr. Kathryn V. Holmes, MD, PhD, to do similar work, looking at host cell receptors for coronaviruses in cats, dogs, pigs and humans, and their contribution to enabling the viruses to infect multiple species.

Coronavirus wasn't a hot topic at the time – the human coronavirus she worked with causes the common cold – but the research gave her an invaluable background for her later work with the COVID-19 vaccine.

In 1997, Tresnan joined Pfizer to do more applied research. Initially, she worked on vaccines for animal health but has since been involved with safety and risk management for a range of medicines and vaccines for humans, including anti-infective drugs, prophylactic vaccines, gene therapies for rare diseases and cancer vaccines and treatments. Most recently, she has worked on determining whether events reported after vaccination in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials are related to the vaccine and constitute side effects. She also contributed to the submission of data for the various Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) applications and FDA approval, and works with the team monitoring reports of vaccine reactions to better understand the safety profile of the vaccine. This resulted in Tresnan co-authoring multiple articles reporting clinical trial data in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In her 24-year career at Pfizer, she says that working on the COVID-19 vaccine has been her greatest contribution to human and animal health. "It's been amazing to be able to be a part of it."

Seeing New Ways to Treat Blindness: William Beltran

When Dr. William Beltran, DVM, PhD '06, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania (UPENN) School of Veterinary Medicine, traveled from Paris to Ithaca to be a graduate student at the Baker Institute, he was in for a bit of a shock. When he applied, he thought the campus was in New York City. But the Baker Institute ended up being just the right place to grow from a clinician to a scientist, so he could pursue his goal of investigating the causes and treatments of retinal diseases.

After completing his veterinary degree and ophthalmology residency at the Alfort National Veterinary College in France, Beltran joined the lab of Dr. Gus Aguirre. "Deciding to train as a graduate student under the mentorship of a veterinary ophthalmologist and a scientist and who had precisely dedicated his career to studying inherited retinal diseases in dogs was the best career decision I ever made," Beltran said. He studied the potential of neuroprotective compounds to slow the death of rod and cone cells in the eyes and developed a new canine model for a common form of retinal degeneration in people.

The institute's research atmosphere —and its location a few miles from the veterinary school — fostered his development as a scientist and allowed Beltran the freedom to approach his research from a novel perspective. Additionally, the Graduate Research Assistantship Program established by former Baker director, Dr. Douglas McGregor, provided the financial support that allowed him to attend Cornell.

Beltran continues to study retinal degeneration in dogs and humans at his lab at UPenn. He and his colleagues have developed gene therapies for five types of congenital blindness. Two therapies are already in clinical trials with human patients; he expects two more will follow. He also serves as Director of the Division of Experimental Retinal Therapies, which brings together veterinary ophthalmologists and vision scientists from his university "to facilitate the development, screening and testing of novel retinal therapies that rescue or restore vision in people and animals." Beltran was also recently elected to the prestigious National Academy of Medicine.

Beltran believes that the Baker Institute’s model of training veterinarians to perform vital research is incredibly valuable, as the COVID-19 pandemic has recently highlighted. "More than ever, veterinary scientists are indispensable in a world that is finally recognizing the intermingling of animal, human and environmental health," said Beltran. "I am convinced that the Baker Institute will continue its long tradition of addressing this need."

Written by Patricia Waldron